Trends: Not All Watches Are Created Equal – Reprise

by Martin Green

Trends rule a larger part of our lives than many of us wish to admit.

Sometimes we follow trends consciously, but often we are subconsciously influenced in the choices we make. The trick for manufacturers is to align themselves with trends while remaining in sync with the original “DNA” of the brand.

This very delicate tightrope walk is unfortunately a necessity all brands must perform. But how successfully they achieve their goals is different for each brand, and sometimes even for each model line within the brand.

On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Chopard in 2010, the brand’s patriarch, Karl Scheufele, put this delicate struggle into words: “My constant challenge has been to hone our sense of observation and to recognize contemporary trends and demands early enough to enable them to shape our business in such a way as to prepare it for the future and for subsequent generations. I view tradition not as a matter of admiring ashes but instead of stirring the embers, of using them to provide a springboard for the future that offers both a sense of continuity and the inspiration to create new things.”

While a tightrope is at least a straight line, trends are often not as clearly visible or delineated. Each product has its own path, yet at the same time the product also needs to fit into the perimeter set by the “DNA” of the brand it belongs to, and even that perimeter is not as clearly defined as we would like it to be.

Rolex Sky-Dweller in yellow gold

The tightrope walk is all about finding borders and stretching the perimeter, but without going too far. While it would be hard to accept a tourbillon made by Rolex, for example, the Sky-Dweller, which is quite complicated for a brand best known for its time-only and chronograph watches, was embraced rather quickly.

Same brand, different watches

While the brand’s “DNA” determines the perimeter, that doesn’t mean that when the different watch collections stay within it they are successful. In some cases, the brand needs to align a collection more with current trends than in others.

The original style of the Omega Seamaster; these particular examples are from 1948 and 1949

Two watch collections by the same brand offer a good example; and both watches can be described as about as successful as it gets in high-end watchmaking: Omega’s Seamaster and Speedmaster have both played prominent roles in the history of watches. The Seamaster by adapting to the way times change (see Element Of Surprise: Omega’s Constellation And Seamaster Were Designed By René Bannwart, Founder Of Corum) and the Speedmaster by mainly staying the same.

A 1957 Omega Speedmaster

The Seamaster sealed its career by always being the right watch for every era it was in. It is a perfect example of a watch that kept in touch with Omega’s “DNA,” adapted in each design in just the right way. In hindsight, these adaptions might seem extreme as we compare the Proplof with the very first Seamaster Reference CK 2518, but for the time when each of these was part of Omega’s collection, they were just right.

Follow the money . . .

Trends equal money.

Trendy equals popular, and that is what people spend money on. Being for-profit companies, watch manufacturers are obliged to follow trends, especially when they are part of a larger conglomerate and registered on the stock market.

Following some trends is easier than others: blue dials have been all the rage lately, and nearly every brand can play into this fairly safely. With the bronze case trend, it already becomes a bit more problematic. The bronze case trend makes sense for brands like Panerai and Tudor because there is historical precedent, but I feel that Montblanc overstretched with its 1858 Chronograph in bronze (see Montblanc’s 2017 TimeWalker And Bronze 1858 Watches: Sporty And Automative With A Healthy Side Of Nostalgia and Montblanc’s 1858 Chronograph Tachymeter Unique Piece For Only Watch 2017: Old School To The Core, And That’s A Good Thing!).

Montblanc 1858 Chronograph Tachymeter Limited Edition

It gets even more delicate when it comes to another trend: skulls! (See Give Me Five! Skulls Grinning From Behind The Crystal At Baselworld 2016.)

While a brand like Corum has no problem incorporating skulls into its watches thanks to perfectly aligned historical precedents, skulls were not such an obvious motif for Bell & Ross.

Bell & Ross BR01-92 Skull Bronze

Bell & Ross managed to work the grinning bones very effectively into its collection, however.

That other brands didn’t follow suit on this is mostly likely because it might have been a short-term win, but a long-term loss: one may “revolutionize” one’s brand by breaking through barriers, but the green grass on the other side might not be as tasty as it seemed.

. . . but don’t follow blindly

This is pretty much what happened with Zenith under its first LVMH CEO (see What Would You Do If You Were The New CEO Of Zenith? This Is What We Would Do . . .).

Before Thierry Nataf was hired by LVMH, Zenith was a niche brand with a loyal following among watch connoisseurs, one that was widely respected for its excellent El Primero movement combined with tasteful designs.

That went all out of the door when Nataf began making rapid changes in the brand’s collection after taking over. Almost overnight, the once low-key insider brand started vigorously courting trends, resulting in a short-term burst of success. But, unfortunately, the balloon deflated about as fast as it inflated.

Zenith Defy Xtreme Zero-G from the Thierry Nataf era (photo courtesy Hess Fine Art)

The reason for that was because Zenith started following trends too much, coming to rely on a single group of customers, which at the time also happened to be located mainly in Russia. When sanctions hit that country hard, Zenith lost ground at an alarming rate, especially since it could not fall back on its original customer base because it was no longer making the products they liked.

It wasn’t all Nataf’s fault, but a large part of Zenith’s problem at that time was trying to grow too quickly by following every trend it could find.

Nataf’s successor, Jean-Frédéric Dufour, immediately recognized the disconnect between the brand, current trends, and its former – now chiefly lost – customer base. He did the only thing able save the brand at that point: pull it completely back into its original “DNA” sphere.

Zenith Chronomaster El Primero Sport Land Rover BAR Team Edition

His success with this was probably one of the reasons that Dufour was offered one of the most coveted jobs in the watch industry: CEO of Rolex. When it comes to trends, Rolex is probably the brand that is closest to being immune to them.

However, even Rolex has made some changes to meet trends, if often reluctantly and only if the trend itself was persistent. Such was the case with the Datejust, which was increased from 36 mm perfection to a somewhat unsatisfying 41 mm – which saw Rolex proving its own point as to why it pays to be conservative.

Rolex Yacht-Master with trendy rubber strap

Creating a landmark watch and then modifying it very conservatively over the following decades has been Rolex’s very successful signature approach.

Fortunately, though, Rolex did not completely shy away from ensuing trends because the Oysterflex bracelet is an absolutely superb contemporary addition to the timeless Daytona as was the long-awaited rubber strap for the Oyster Perpetual Yacht-Master.

Trend-defying characteristics

To come back to Omega, though, what is it exactly that made the Seamaster have to go through so many changes to maintain its success while the Speedmaster didn’t?

There is no definitive answer to this: there are just too many variables in the concept of trends making a concrete answer too elusive. However, NASA selecting the Speedmaster as its official timekeeper, making it the first watch worn on the moon, gave it a status that translated into consistent demand even decades later.

Omega did introduce Speedmasters that were more in tune with the trends of their era, like the Mark II and Mark III, but none of them could eclipse the original, which Omega faithfully retained in the collection with only minor modifications in the decades to follow.

Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch Professional Chronograph

What makes the Speedmaster a watch that can defy trend? First and foremost being well built to a high quality greatly helps.

Secondly, the watch has universal appeal. This is already a slippery slope because what is universal appeal? I would characterize this as being respected for its qualities and design, even by those who don’t particularly care to own or wear one.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak with blue Tapisserie dial

A prime example of universal appeal is the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, which has pretty much retained its original shape since its inception in 1972, enjoying continued success from its conception to the current day.

Patek Philippe Reference 5711/1P Nautilus

The same can be said of the Patek Philippe Nautilus, which was born in 1976. Both of these now-iconic designs of course emanate from the drawing board of legendary watch designer Gérald Genta, who also created the IWC Ingenieur, another long-lasting design from the 1970s.

IWC Ingenieur with black ceramic bezel and carbon fiber dial

While Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe have basically left their icons untouched, IWC let the Ingenieur sail the sea of trends. It would be very interesting to see what would have happened if the brand hadn’t done that. For a little more on the 1970s history of these sports watches, including the Vacheron Constantin 222/Overseas, see A History Of Vacheron Constantin’s Overseas Line, Culminating In 2016’s Worldtimer.

The influence of Lady Luck

There is another aspect of trends that we don’t like to talk about: the influence of Lady Luck. When you work hard on something and it becomes a success, it is hard to share credit with her.

Audemars Piguet took a big risk when it introduced the Royal Oak back in 1972, offering it back then at an enormous price for a steel watch. If the public had rejected it, there is no way of knowing where Audemars Piguet would stand now.

What would have happened if the Speedmaster hadn’t become NASA-certified and the first watch on the moon? Most likely it would have followed the trends a bit more closely as the Seamaster has done over the course of its career.

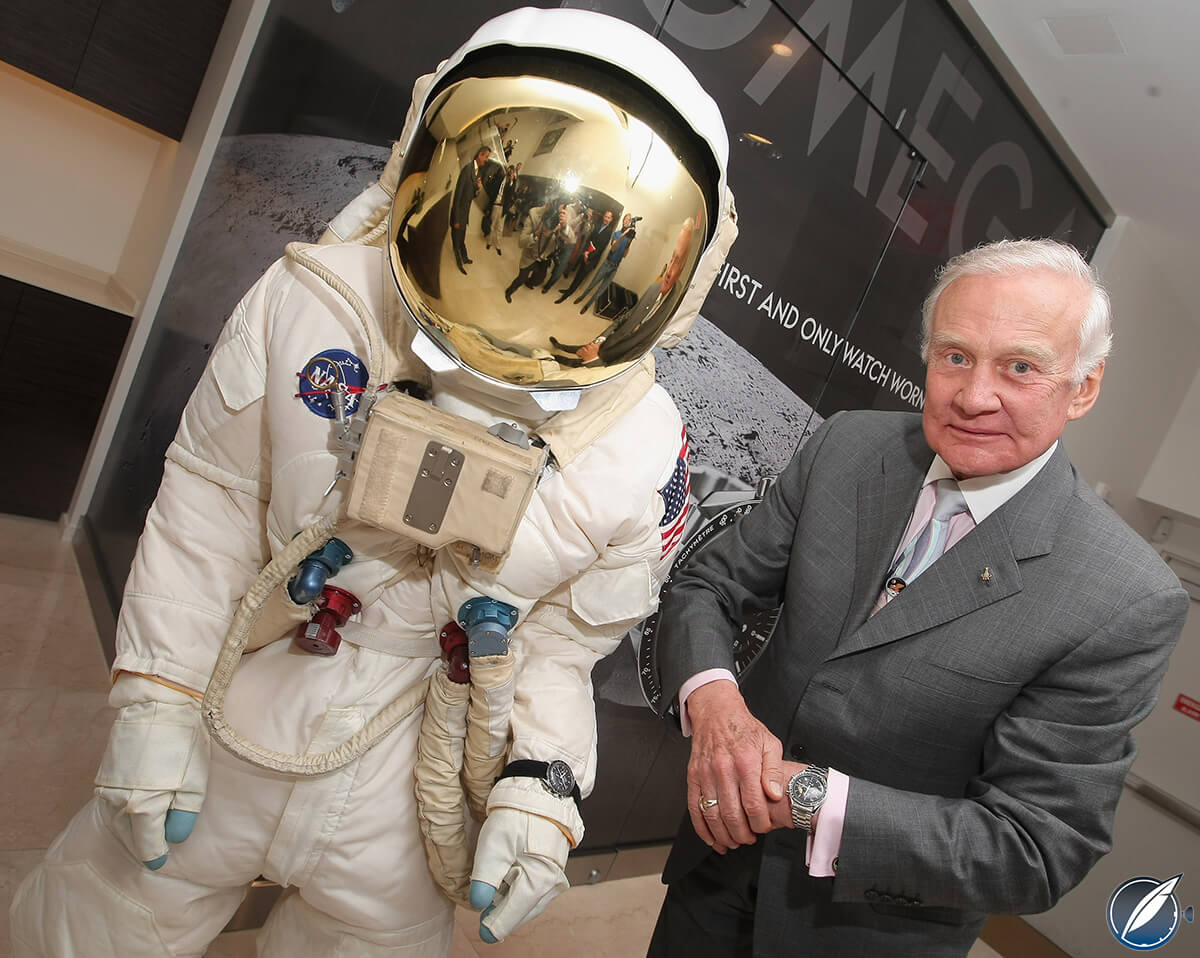

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin and his Omega Moonwatch (photo courtesy Omegawatches.com)

Of course, a lot of these what-ifs are just that, indicating that trends and success are closely related, yet that it is very difficult to pinpoint the exact collaboration between them, which makes the approach that Karl Scheufele outlined at the beginning of this article by far the most prudent path.

* This article was first published on October 28, 2017 at Trends: Not All Watches Are Created Equal.

You may also enjoy:

The Death Of The Dress Watch: Is It Time To Write Its Obituary?

My view is that the Nautilus and to a lesser extent the Royal Oak are plain, boring, and incredibly overpriced.

I think we have to accept that the wristwatch is a century-old technology, providing a very small amount of information, worn on a part of the body that has a specific geometry.

Manufacturers keep trying to un-necessarily re-invent the wheel when it has become quite clear for decades that the classics are established. Most people buy a cheaper, slightly redesigned alternative to a few designs.

The key to almost every successful watch company is producing straightforward legible designs with reliable engineering at a perceived fair price for the level of sophistication offered.