Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité: The Most − If Not The Only − Fully Handmade Watch Available Today

by Ian Skellern

“Watchmaking” and “watchmakers” are perhaps two of the biggest misnomers in the world of horology today. The day-to-day work of the vast majority of watchmakers, even the very best of them, would be more accurately described as watch assembling or movement regulation rather than watchmaking.

And that’s not to demean their craft, but to convey a clearer description in the reader’s mind of what virtually all conventional watchmakers are really doing.

Handmade: the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

“Handmade” is another term liberally used in the world of horology instead of “hand assembly,” and its misuse decreases the real value implied by “handmade” year after year, decade after decade. I won’t bother to get into what counts today as “hand-finishing” beside to say that it’s more viewed in marketing copy than inside a wristwatch.

The skills involved in making a beautifully finished high-end watch by hand are steadily disappearing. As Philippe Dufour often laments, when an experienced watchmaker retires or dies it’s like pulling a page from the “Book of Horology” . . . and the pages are not being re-written or replaced (see Why Philippe Dufour Matters. And It’s Not A Secret).

Today, there is also talk about the fact that watches fitted with high-tech components in silicon and other exotic materials will not be able to be repaired by future generations of watchmakers using readily available machines.

Handmade: the distinctive movement of the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité is visible through the display back

There are still a few watchmakers who can recreate components and repair watches and clocks from the age of Abraham-Louis Breguet and beyond using machines and techniques that the great watchmakers of the past would not only recognize, but could probably use with little or even no training.

But there are not many watchmakers today with the skills to make components using traditional hand-operated machines to the incredibly demanding tolerances required in a precision wristwatch.

Making precision parts for clocks is difficult, for pocket watches even more so, but to reliably and consistently hand-make minuscule components to the micron tolerances required for an accurate wristwatch is incredibly demanding and simply impossible for most.

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

Temperature, humidity, time of day, and even the mood of the watchmaker/machinist can affect the dimensions of the components being machined by an incredibly tiny amount, but that’s often enough to make the parts unusable.

And if there are few watchmakers and machinists capable of creating by hand all of the components required for a traditional wristwatch, there are even fewer of these artisans today who are actually making complete precision wristwatches in numbers higher than one-offs.

Naissance d’une Montre, Le Garde Temps at SIHH 2016: a handmade watch that is sadly no longer available to buy

In fact I know of only three watchmakers doing this today: one is Michel Boulanger, who has completed his “school watch” for the Time Aeon Foundation’s Naissance d’une Montre project under the tutelage of Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey, and Philippe Dufour. The other two are Dominique Buser and Cyrano Devanthey, who are hand-making watches under the brand name Oscillon.

The 11 handmade Naissance d’une Montre timepieces sold out a year ago: that “school watch” sold for $1.46 million in a May 2016 Christie’s auction. So the only fully handmade haute horlogerie wristwatches available to buy today are from Oscillon.

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

But be warned, making watches by hand like this is a very slow and very expensive undertaking, for example the 11 Naissance d’une Montre collection timepieces sold (past tense) for CHF 450,000 each. Oscillon does not expect to make more than five watches per year, so the term “available” really means available to a few serious collectors with deep pockets.

The birth of Oscillon

A long, long time ago − the mid-1990s − in a watchmaking school far, far away − in Solothurn, Switzerland − two young men in their first year at watchmaking school discussed the possibility of making their own watch from scratch.

However, as their horological education progressed over the years, making a clock from scratch seemed more realistic than making a wristwatch. But then they realized that even making a clock by hand using traditional tools and techniques required a lot more skills, experience, and machines than either had at the time.

However, over the following years they both gained experience and steadily built up their collection of watchmaking lathes and machines.

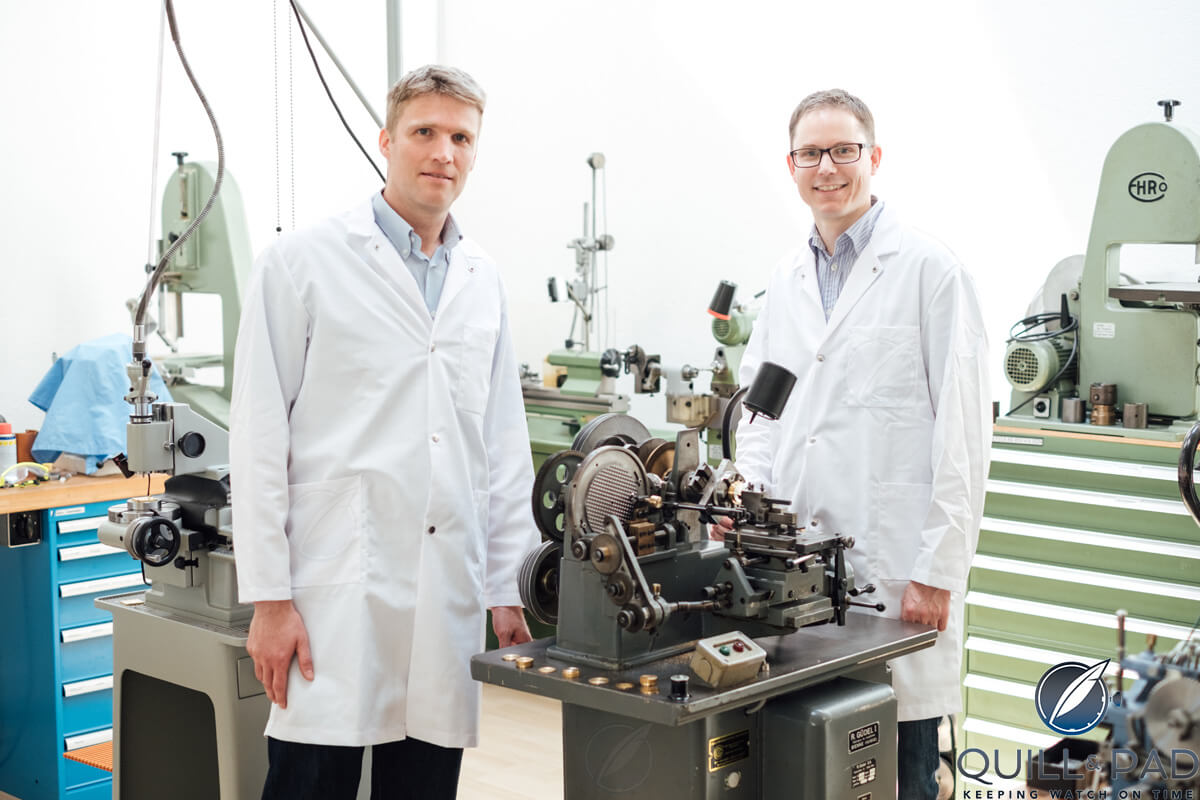

Oscillon founders Dominique Buser (left) and Cyrano Devanthey

The two watchmakers were Dominique Buser and Cyrano Devanthey. And although each went his own way after graduating as nascent watchmakers in 1994, they remained friends over the years and stayed in touch.

Another friend of theirs from the Solothurn watchmaking school was Felix Baumgartner, who with his brother Thomas and Martin Frei went on to found Urwerk.

Dominique Buser

After graduating as a watchmaker in 1994, Buser went to Geneva to work for Vacheron Constantin. In 1996 he moved back up to Basel and Zurich, where he worked part-time until 2004 for a jeweler/watch retailer. Buser worked part time because he was curious about the workings of the universe and decided to study physics at the University of Zurich, graduating in 2003. Just in time to help develop the Urwerk Opus 5 for Harry Winston (see The Harry Winston Opus Series: A Complete Overview From Opus 1 Through Opus 13).

Opus 5 by Felix Baumgartner/Urwerk for Harry Winston

In 2003 Urwerk had ambitiously committed to creating the Opus V for Harry Winston, the last Opus under the originator of the groundbreaking series, Maximilian Büsser, who left Harry Winston in late 2005 to create his own brand, MB&F. Urwerk’s Felix Baumgartner and Martin Frei knew that they would need a talented movement designer to turn their complex idea into reality.

At this stage Buser had no experience as a movement designer, however Baumgartner thought that with Buser’s watchmaking experience, grounding in physics, and knowledge of sophisticated computer programs, how hard could it be? He convinced his friend to set up a company and workshop near in Buchs AG (near his home village) and learn how to use a 3D CAD program.

Talk about jumping and learning to fly on the way down! Buser’s very first project as a movement designer was the complex Opus V, and his atelier became Urwerk’s skunkworks R&D department.

Since 2011, in parallel with his day job, Buser has also taught one day a week at the Zeit Zentrum (“Time Center”) watchmaking school in Grenchen, Switzerland (where it all started), giving classes on technical drawing, CAD, and laboratory and production techniques.

Cyrano Devanthey

Upon graduating as a watchmaker in 1994, Devanthey worked in Zurich for Les Ambassadeurs, one of Switzerland’s most prestigious watch retailers, where he both repaired and sold high-end wristwatches. In 1998 he went to Omega in Bienne, where he first worked as a technical advisor training Swiss watchmakers and then as head of Omega’s customer service department in Switzerland.

This led to him transferring his Swiss experience to Omega’s international markets, where he managed training for Omega watchmakers around the world as well as reorganized Omega’s international service centers.

In 2005, Devanthey was made responsible for Omega’s Cellule Haute Gamme (“top of the range” department), in which one of his main roles was managing the production of the Omega Central Tourbillon, the world’s first production wristwatch with a central tourbillon.

The Urwerk UR-110 in the Eastwood version, which looks eminently British with a Timothy Everest tweed strap

In 2009, 15 years after leaving the watchmaking school that had brought them together, Devanthey joined Buser at Urwerk’s R&D atelier in Buchs, where his first responsibility was the development of the UR-110.

Experiment ZR012 Black by C3H5N3O9 (photo courtesy Guy Lucas de Peslouan/ArtSight)

Another of his projects was developing and making Experiment ZR012 for C3H5N3O9, a joint venture by Urwerk and MB&F.

Dial of the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

The birth of Oscillon

Over the decade and a half since graduating as watchmakers, both Buser and Devanthey had each amassed quite a collection of manual watchmaking machines and tools that they used to make components for their own projects and prototyping parts and mechanisms for Urwerk.

But they had never forgotten their dream, and in 2012 started seriously working on making their own wristwatches by hand using only traditional tools and techniques.

To them, making their own watch meant making every component they possibly could by hand. This included all of the movement components except for the jewels, Incabloc balance shock protection, and the raw (constant force) mainspring and balance spring, though they did cut and shape the springs.

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité on the wrist

They even made their own guilloche dial and case, apart from the sapphire crystals and rubber gaskets.

One component that they haven’t quite (yet) mastered making to the precision required is the escape wheel. This critical component in steel is extremely thin and light with a very complex tooth shape. And the teeth must be faceted to reduce friction. That said, they are making their own escapement lever. Once they are happy with their own escape wheels, they will (if requested) replace the third-party escape wheel in any early watches at their first service.

Case band view of the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

It isn’t just mastering the complex manual machines that is a time-consuming challenge, tools must be made to hold the complex components while they are being machined and worked. Just making one tool can take a week. And then it may be discovered that it’s not quite good enough and the whole process must be repeated.

The name “Oscillon”

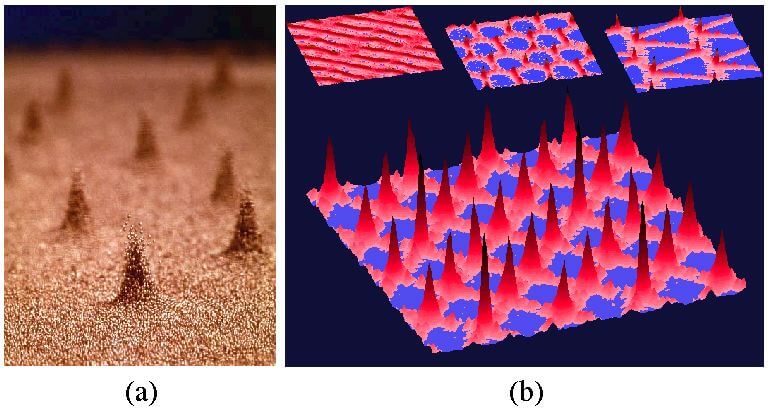

You may find the video below showing oscillons being created easier to understand than the following words, but for the physics nerds out there: an oscillon is a soliton-like phenomenon occurring in granular media. Oscillons result from vertically vibrating a plate with a layer of uniform particles placed freely on top. The effect was first reported by Michael Faraday in 1831.

(a) Array of oscillons from a granular vibration experiment and (b) patterns from simulations of 32,767 idealized particles (image courtesy Paul Umbanhowar, Northwestern University and Harry L Swinney, University of Texas, Austin)

The video above highlights how the patterns created by oscillons inspired the complex guilloche pattern on the dial of Ocillon’s l’Instant de Vérité timepiece.

What is l’instant de vérité (“the moment of truth”)?

When making components by hand, the skilled artisan has a vision of what the perfect part should look like when it’s finished. To achieve that the challenge is twofold:

1. To not lose nerve before executing the last step because the line between excellent and perfect is very fine and few, if any, will notice the difference. It’s tempting not to take that last step, but that temptation must be resisted.

2. Going for perfection but failing and destroying the component in the process because there is also a very fine line between perfection and destruction.

That final step is l’instant de vérité, the moment of truth. The artisan not only has to have enough knowledge and skill to be able to realize his or her vision of perfection, but be bold and brave enough to attempt the summit of the craft.

And to face l’instant de vérité over and over for each and every component and not be discouraged by failure, but to learn from it.

The Oscillon workshop has bins full of unusable parts thanks to l’instant de vérité. The challenge of perfection is not always met successfully, but it is always faced.

The watch: l’Instant de Vérité

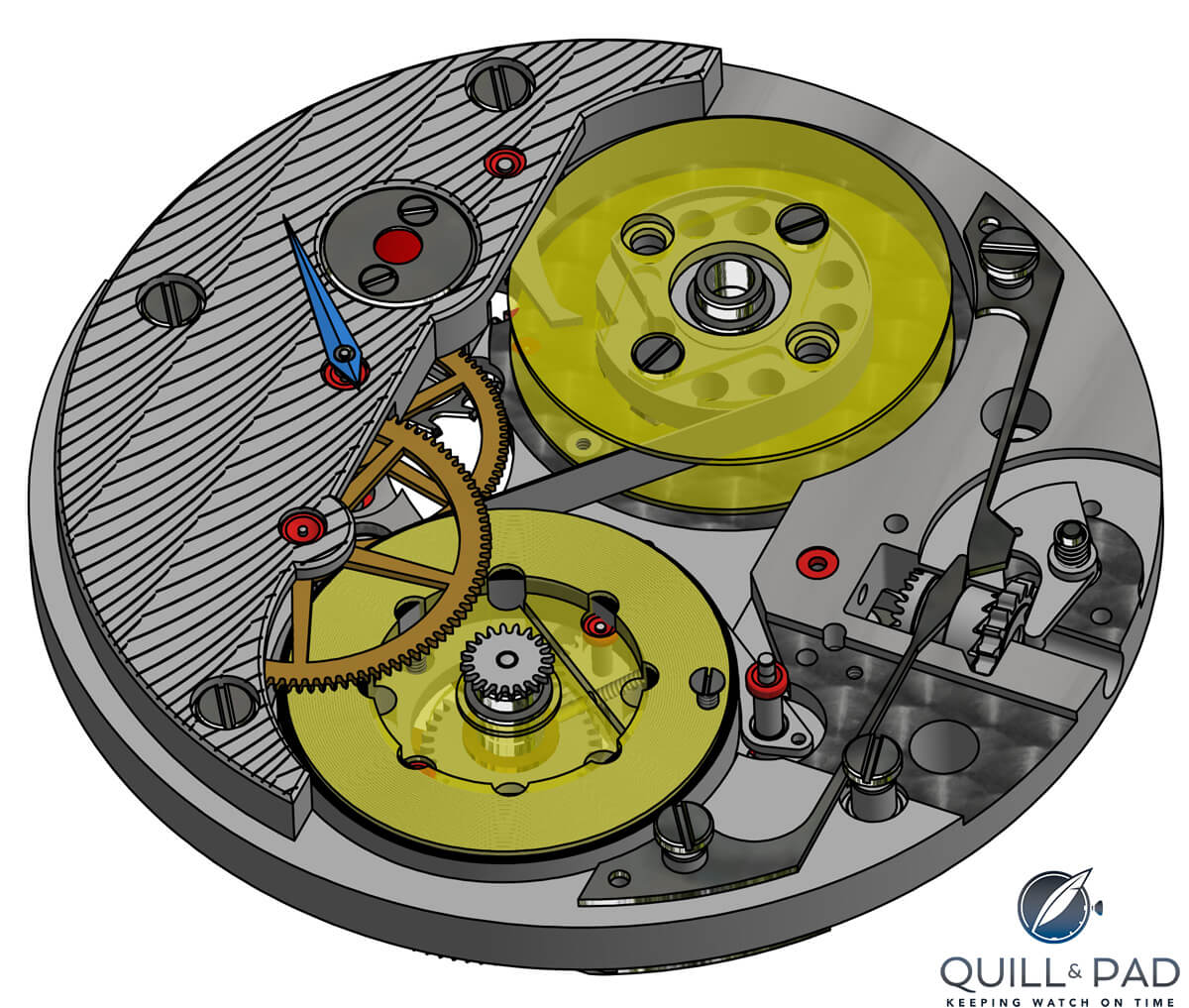

The aim for l’Instant de Vérité was to make a relatively simple watch with traditional hours, minutes, small seconds, power reserve (a very healthy 68 hours), and a non-traditional Tensator constant force mainspring.

Movement of Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité No.1

This is first time this type of constant force mainspring has ever been (successfully) used in a wristwatch. It also has an unusual bow tie-shaped balance wheel.

Tensator mainspring

A Tensator spring has the unique property of wanting to return to its original coiled shape when wound against its natural curve onto another drum. A Tensator spring has two quite unique characteristics:

- Unlike a normal mainspring, there is little to no friction between the coils.

- There is no change in torque as the spring is unwound. The spring is first wrapped on a smaller storage drum and an end fastened to a larger torque drum so that as it unwinds its curve is reversed. As the spring unwinds onto the torque drum it is winding against its natural shape so its tendency is to return to its natural state on the storage drum.

These two characteristics ensure that the Tensator spring always winds/unwinds with a constant force.

How a Tensator constant force spring works

The Tensator spring releasing constant force is what winds your vacuum cleaner’s electrical cord back at a constant speed or the T-bar when you release it at the top of a ski slope. If these were not constant force springs, they would pull very hard and fast at the start but slow down and be unlikely to wind in completely at the end.

Tensator-type constant force springs have been used in clocks because constant force from the mainspring is much better than having non-linear torque, but it hadn’t been used in wristwatch movements before due to the challenge of making them small enough and the lack of information about their properties at smaller scales.

However, Oscillon didn’t just want to copy what was done before in traditional wristwatches, but to advance horology as well, and the challenge of developing a movement with a constant force mainspring looked promising. But it was by no means easy.

With regular watch mainsprings there are well-developed, tested formulas for working out the size, length, shape, and power of mainsprings, but with the small Tensator constant force spring Oscillon had to start from scratch to learn all of the properties regarding the optimal size, length, and shape the spring

Drawing showing how the large constant force mainspring fits into the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité movement

Buser and Devanthey also had to change the differential system from what they had planned as the spring didn’t behave at all as they expected. When they ordered the first springs they had no idea if they would even be suitable.

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

The dial

One of the most demanding machines to master was the brocading machine, which is used to make the dials. This is the same process Audemars Piguet uses to make its Royal Oak Tapisserie and Grand Tapisserie dials.

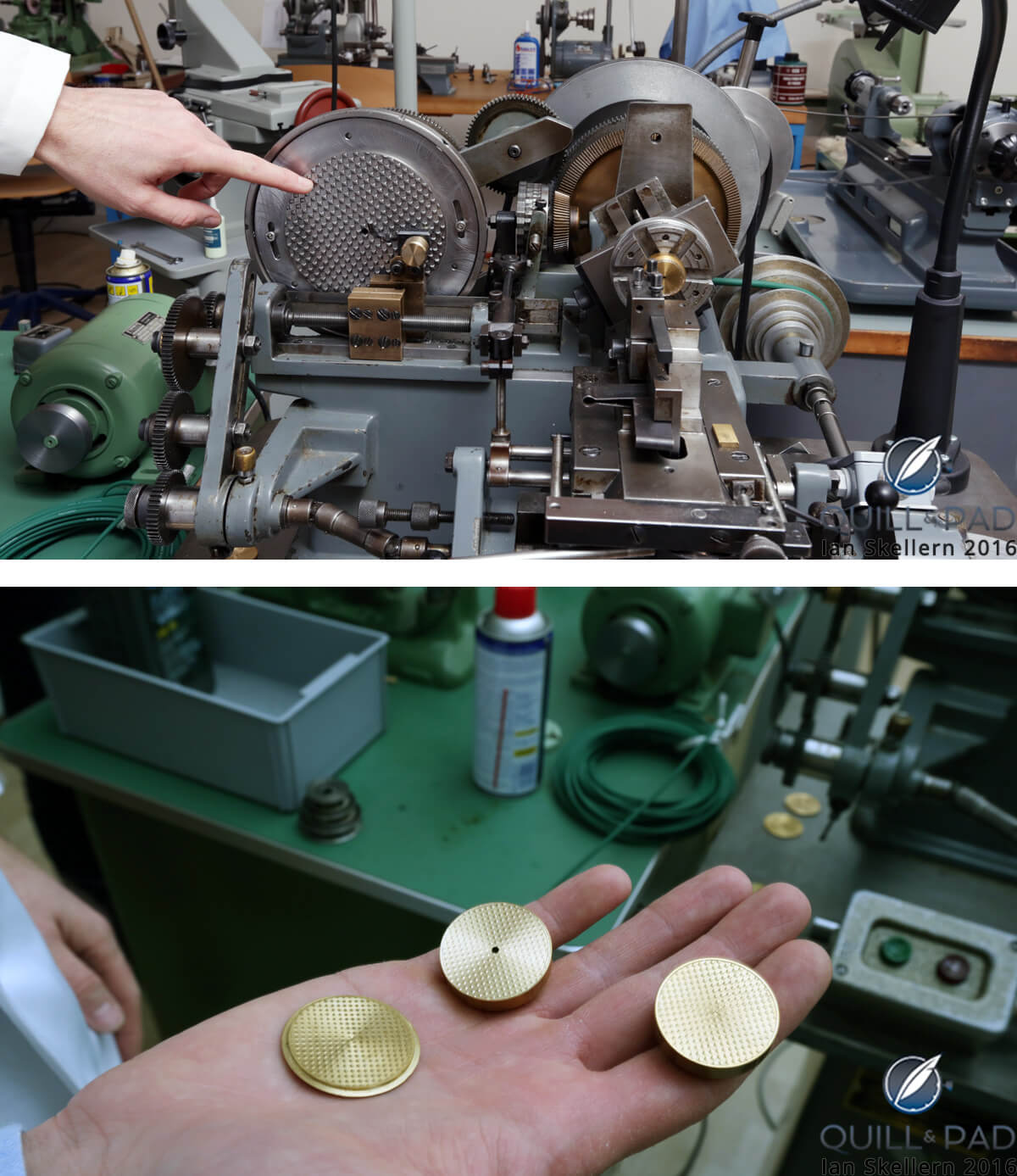

The brocading machine used to create the guilloche dials of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

It’s an amalgamation of a guilloche rose engine and a medallion copying machine, combining milling operations commonly undertaken on a lathe or cutting machine. There are many parameters to adjust, including the shape of the palpate pin, the shape of the cutting tool, and the running speed, just to mention a few, all of which must be absolutely correct to ensure a good result.

A close look at the dial of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

The oscillon-inspired guilloche pattern on the dial of l’Instant de Vérité is particularly complicated because of the complexity of the shapes and engraving.

The brocaded dial of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

As with many of the machines Oscillon has collected and refurbished, its brocading machine has an interesting history. It was originally manufactured near Bienne, which is about 80 kilometers away from the Oscillon workshop. But Buser and Devanthey found this one in the USA (on eBay), so had it shipped and trucked back to where it started.

Mainplate

The most complex component of the l’Instant de Vérité movement to produce by hand is the mainplate, which demands total concentration.

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité mainplate before and after

Unlike mainplates created on a CNC machine, which once programmed need little further input, every point, hole and recess on the l’Instant de Vérité mainplate has to be manually reset on three axes. The slightest error on any adjustment means more scrap for the bin.

Pallet fork

The escapement’s pallet fork is yet another particularly demanding component to produce by hand as it is extremely thin and delicate, yet its angles and dimensions must be absolutely perfect or the movement will not simply run fast or slow, it is unlikely to run at all.

Balance wheel

Then there’s that unusual bow tie-shaped balance “wheel” with regulating screws. A balance wheel must be perfectly balanced if it is to oscillate isochronally (with a consistent rate). Without a perfectly balanced balance wheel no movement can keep accurate time.

Movement of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité showing the distinctive bow tie-shaped balance wheel at the top and the large differential for the constant force spring at the bottom

If you have ever seen a car wheel balanced after fitting new tires, you will know that the wheel is spun quickly on a machine that indicates where and how much weight must be added on the rim to balance the wheel.

The procedure is similar with the balance wheel of a watch movement.

The distinctive, unique balance wheel of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

But what happens when the machine indicates a little mass should be added or subtracted on the rim where there is no rim at all? The adjustments required are demanding to say the least, and from what I understand involve a bit of witchcraft (I’m sure I saw a bottle labeled “Eye of Newt” on a shelf).

View from the back of the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

There are six different-sized screws among the l’Instant de Vérité movement’s 42 total screws, each one made by hand. While making screws is extremely time-consuming, the quality is much better and each screw is perfectly sized for its role.

When making watches in small quantities but buying screws in the large numbers they are sold in, small brands tend to round up or down to limit the stock (read: investment) carried in screws, so they are rarely “the exact right size” This is why Greubel Forsey makes their screws in-house (see Greubel Forsey And The Proverbial Loose Screw: An Anniversary Tale).

Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité isn’t a particularly complicated watch (though that constant force mainspring is), nor is it a wild design likely to catch the eye from across the room.

Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

Even the buckle of Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité is handmade

However, it stands head and shoulders above every other watch currently available in that it is the most handmade wristwatch available to buy today. L’Instant de Vérité isn’t just one of the best handmade wristwatches available to buy today, it is THE ONLY handmade wristwatch available today.

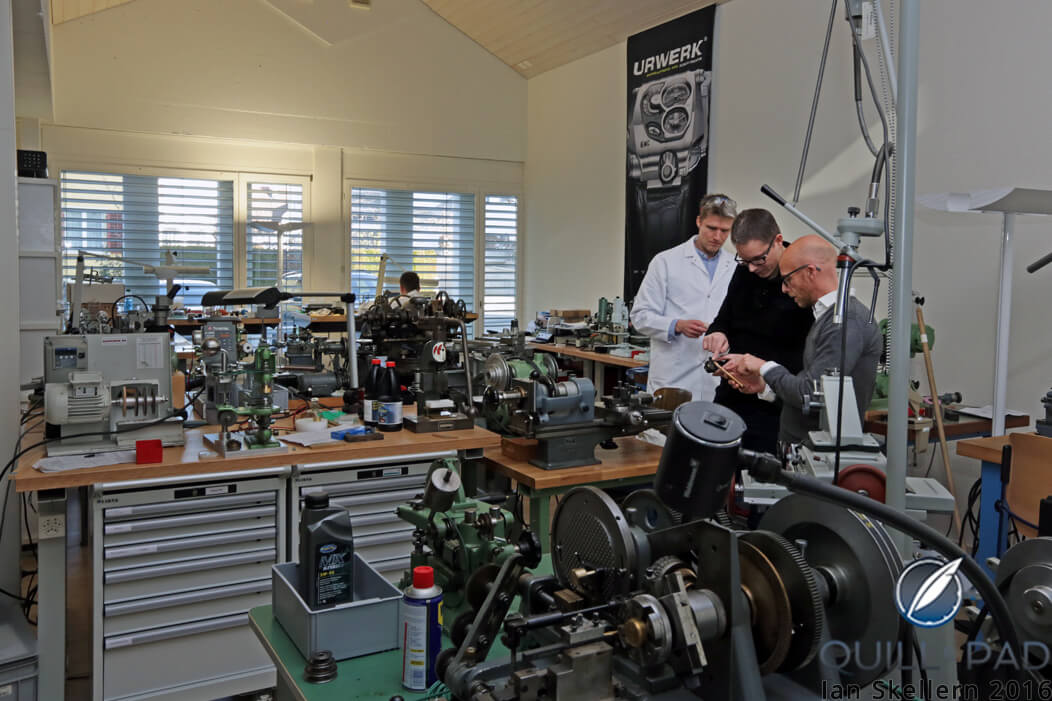

In the machine-filled Oscillon workshop in Buchs, with Dominique Buser (left) and Cyrano Deventhey talking to David Bernard (Complitime/Greubel Forsey/Time Aeon Foundation)

And thanks to Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité, the skills learnt in its creation are being passed on to a new generation of watchmakers. Hopefully in 200 years there will still be people able to make watches much like Abraham-Louis Breguet did, using many of the same tools and techniques.

Oscillon, Felix Baumgartner, and the Time Aeon Foundation

The Time Aeon Foundation is dedicated to preserving and transmitting traditional watchmaking skills and knowledge. Its most high-profile project to date has been Naissance d’une Montre – Le Garde Temps (see Le Garde Temps Project With Greubel Forsey And Philippe Dufour: Where It’s At And Where To Next), which saw Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey, and Philippe Dufour (as well as many others) teaching French master watchmaker and teacher Michel Boulanger how to make a watch by hand. That four-year project has Boulanger now in the process of making the 11 timepieces. He is also sharing what he has learned with other watchmakers and his watchmaking students in Paris.

Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité

Earlier this year, Robert Greubel and Felix Baumgartner were talking and the subject of perpetuating traditional watchmaking skills and techniques came up. Greubel spoke of what the Time Aeon Foundation was doing with Naissance d’une Montre, and Baumgartner casually mentioned that Urwerk’s development team was doing something similar. And that Buser and Devanthey were also sharing what they have learned hand-making watches with two young recently qualified watchmakers, David Friedli and Jonas Plüss, as well as with the students in the watchmaking classes they teach.

So it’s no surprise that when Oscillon and the Time Aeon Foundation learned of each other’s existence earlier this year, they soon set to work on developing a project together. That project will be announced ahead of SIHH 2017, and Buser and Devanthey will be conducting demonstrations at the fair under the auspices of the Time Aeon Foundation and the Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie in a booth near the entrance to the Carré des Horlogers .

Fitting the dial to the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité No.1

While Oscillon is a brand run out of Urwerk’s research & development workshop in Buchs, it is not at all an Urwerk sub-brand. But Urwerk co-founder Felix Baumgartner has more than a casual passing interest in preserving, encouraging, and transmitting the knowledge and skills of traditional handmade watchmaking.

Baumgartner is a third-generation watchmaker and he grew up in a household full of his clock restorer father’s tools and machines. There’s a reason that the first Urwerk watch had a round case; it had to as it was made, along with many of the movement components, on his simple watchmaker’s lathe.

While you do need a lot of complex machines to make a traditional handmade watch as sophisticated as Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité, a good lathe is nearly all that is needed to make a simple handmade watch. Baumgartner encouraged and supported Buser and Devanthey in the Oscillon project and is passionate about encouraging young watchmakers to learn and master traditional techniques and skills. To further that end, Baumgartner has recently become a member of the Time Aeon Foundation.

Last word

What makes (some) watches so special to me aren’t the watches themselves but the stories they embody. And few timepieces offer as rich a narrative as the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité. Oscillon’s chapter one is just beginning and the authors are already working on chapter two. I’m hoping this will be a thick book, and I’m sure Philippe Dufour is happy to learn that new pages are still being written in the “Book of Horology”!

Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité is available exclusively though the Türler watch and jewelry boutique in Zurich, and Buser and Devanthey welcome aficionados of traditional fine watchmaking to visit their workshop in Buchs (south of Zurich), where they will be pleased to explain how and why they work as they do for Oscillon.

To further highlight just how serious Oscillon takes “handmade,” even their business cards are hand-printed on an old machine one precious card at a time!

Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité on the wrist

For more information and/or to contact Oscillon, please visit www.oscillon.swiss, www.tuerler.ch and www.timeaeon.org.

Quick Facts Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité

Case: 40 mm in red gold, handmade on traditional machines, screw-on display back

Dial: guilloche dial in German silver with pattern inspired by oscillons; hand-sculptured and hand-polished hands in steel

Movement: manually wound manufacture caliber with Tensator constant force mainspring, all components handmade except for jewels and escape wheel (though the latter is coming), constant force spring and balance spring formed by hand, superlative hand-finishing of components

Price: 162,800 Swiss francs, available exclusively though Türler Uhren und Juwelen in Zurich

* This article was first published on December 22, 2016 at Oscillon’s l’Instant de Vérité: The Most − If Not The Only − Fully Handmade Watch Available Today (Felix Baumgartner And Time Aeon Foundation Are Involved)

You may also enjoy:

Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1: Hands Breathing Life Into Metal

The Watch That Changed My Life: The Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillon By Daniel Roth

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Ok, the article was written in 2016. Perhaps a postscript would be in order, to mention that there are now several young watchmakers who make ‘handmade’ (a slippery term if ever there was one) watches without the use of CNC.