Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock: A Mechanical Masterpiece By A Mechanical Mastermind

Politics, ideologies, and culture wars: these are the things that I most dislike about the world we currently live in.

There are so many wonderful and incredible things in every corner of our earth that it is truly a shame we aren’t one big happy family sharing this beautiful blue planet. Imagine being able to travel anywhere and meeting anyone without fearing for your safety because of religion, nationality, or which bathroom you use.

A whole world of adventure would await you!

But instead we live in a world struggling with fear, one wrong move away from an armed conflict. As an American living under an increasingly controversial administration at the beginning of 2017, the list of places that I can visit in the world and feel comfortable in seems to shrink by the day.

Normally this would have nothing to do with horology as Switzerland is neutral, Germany and England are part of my heritage, and the Japanese are great friends with the United States of America.

And while that covers almost all of the major horological centers of the world, there is one place that consistently produces incredible mechanical wonders where I may or may not be so welcome: Russia.

The sure-to-be-legendary Konstantin Chaykin and his eponymous manufacture reside in Moscow, and it is there that he makes some of the most original watch and clock creations on planet earth. This should make his workshop a top destination for any horology nut.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

His latest masterpiece, the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock, isn’t designed for the wrist but for the mantel, and it provides further evidence that the man I dubbed the “Wonderboy Russian Watchmaker” in Why Independent Russian Watchmaker Konstantin Chaykin Is A Movie Star is one of the greatest watch- and clockmakers in the game today.

Astronomically complicated, literally

The statement that Konstantin Chaykin is one of the greatest players in the world of horology today is sure to ruffle some feathers, but after one look into the complications in the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock, it should be clear that the designation stands.

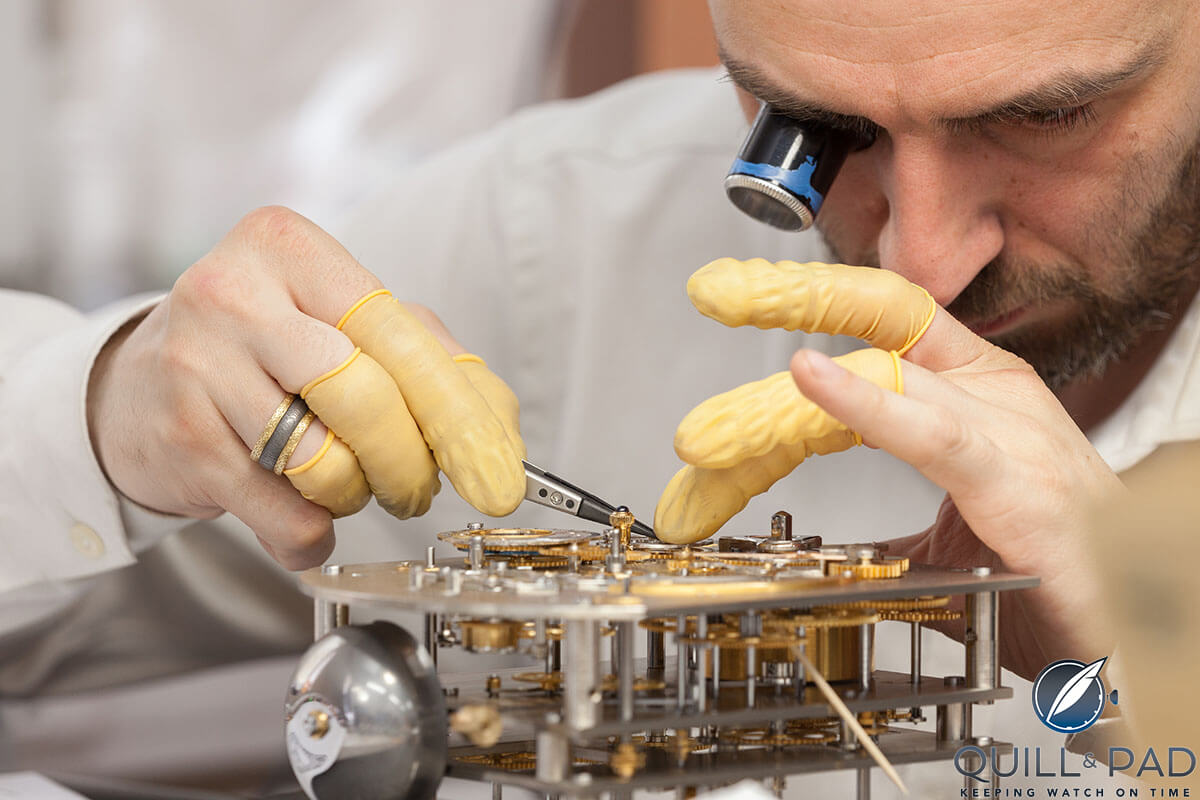

Konstantin Chaykin working on the movement of his Moscow Comptus Clock

So, first off, what is the big deal about the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock? Well, the fact that it has 26 indications, including 12 astronomical indications (two of which have never been seen before), which resulted in five different patents, is a pretty good place to start.

The clock is an expansion on an earlier piece from 2015 featuring the notoriously difficult Eastern Orthodox Easter indication. Computing an accurate date for Easter is no simple task, as it is first based on two different calendars (Gregorian and Julian calendars) depending on where you practice.

After that, the date is determined by the first Sunday after the ecclesiastical (not astronomical) full moon on or after March 21 (fixed date of the vernal equinox), which allows for the date to differ between the two calendars.

The Moscow Comptus Clock presents the date of Easter based on both the Julian and Gregorian calendars, which means that not only one, but two calculations have to be mechanized into a combined display, as the two calendars can converge and diverge over time based on the method of calculation.

Konstantin Chaykin working on the movement of his Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

This is demonstrated on the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock via a single retrograde indication over two offset scales. Each scale includes double references to certain dates, the outer scale repeating days 22-25 and the inner scale repeating days 4-8 to allow for the diverging dates from each calendar’s calculation. On each side of the dial are two windows that change to show the correct month for each scale as it changes.

Diamond-studded sun hand displaying the equation of time on the Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

But the best part about the clock is that the incredible Eastern Orthodox Easter indication is just the tip of the iceberg.

As previously stated, the clock features 12 astronomical indications over the four different faces, and on the same face as the Easter indication is a “standard” moon phase indication with age of the moon.

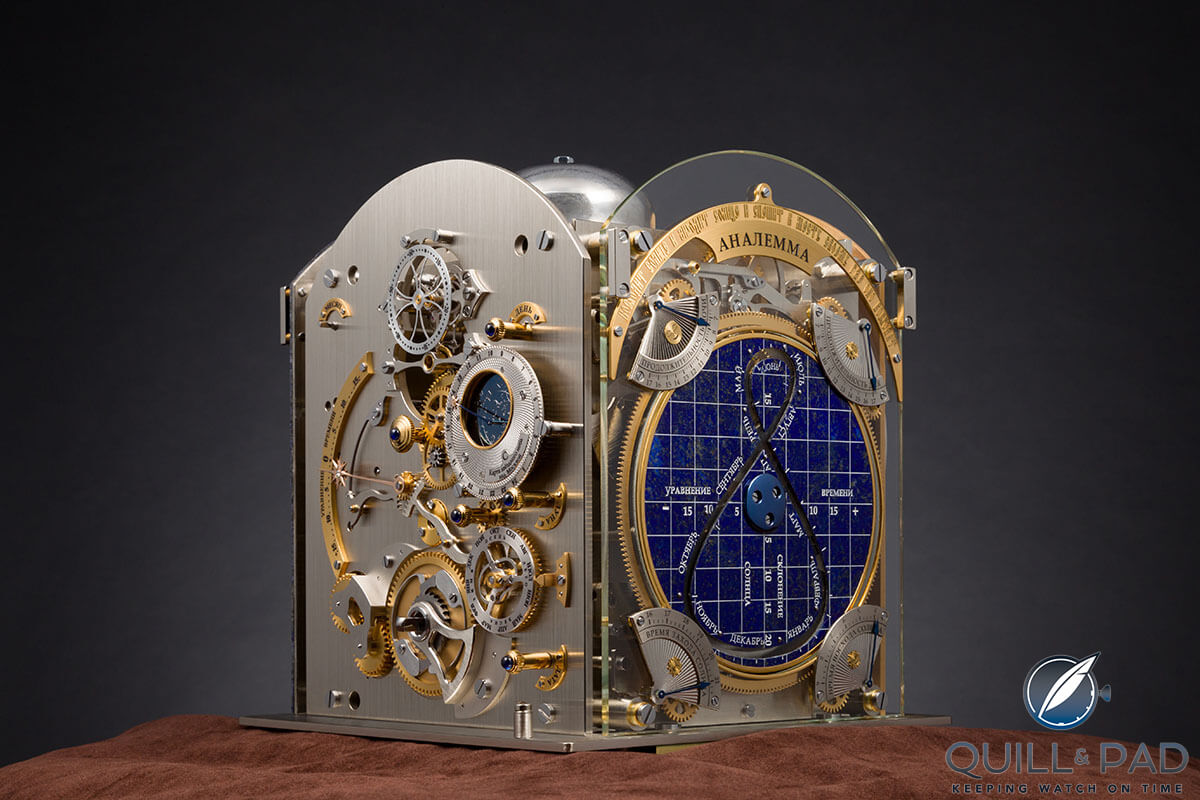

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

This is also tied to the perpetual calendar on the dial digitally showing the current year, analogue day of the month, and current leap year cycle, which is needed to calculate the complex shifting date of Easter. This single face of the clock has enough mechanical magic behind it to excite any horology nerd, so the rest of the faces are more than enough to make your head explode.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

The marvels just keep coming

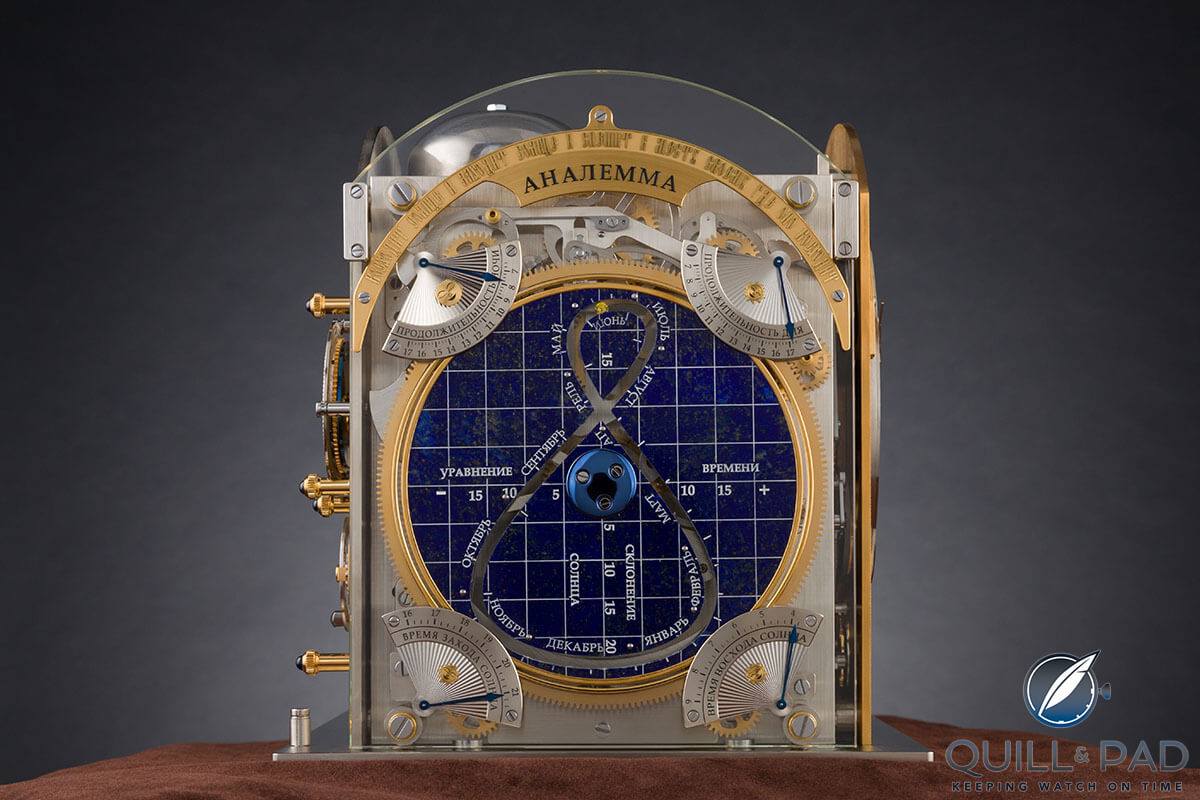

Moving clockwise around the clock (what a weird statement to make), the next face shows the analemma module.

A confused reader speaks up: “I’m sorry, could you repeat that?”

Sure thing! The analemma module is an indication displaying the sun’s deviation from its average motion in the sky. The display of this concept has been floating in Chaykin’s head for more than nine years, and a variety of mechanical solutions were discussed and prototyped before the current and most elegant solution was developed.

Movement of the Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

However, that explanation hardly describes what it is.

So here we go.

Throughout the year, the sun moves faster and slower through the sky relative to the earth’s place along an elliptical orbit and the relative position of the earth’s 23-degree tilt of the axis to the plane of our orbit around the sun. This changes daily, causing the actual time (apparent solar time) and the averaged time our clocks measure (mean solar time) to diverge, with apparent solar time moving ahead or behind mean solar time.

The resulting calculation to measure this difference is called the equation of time.

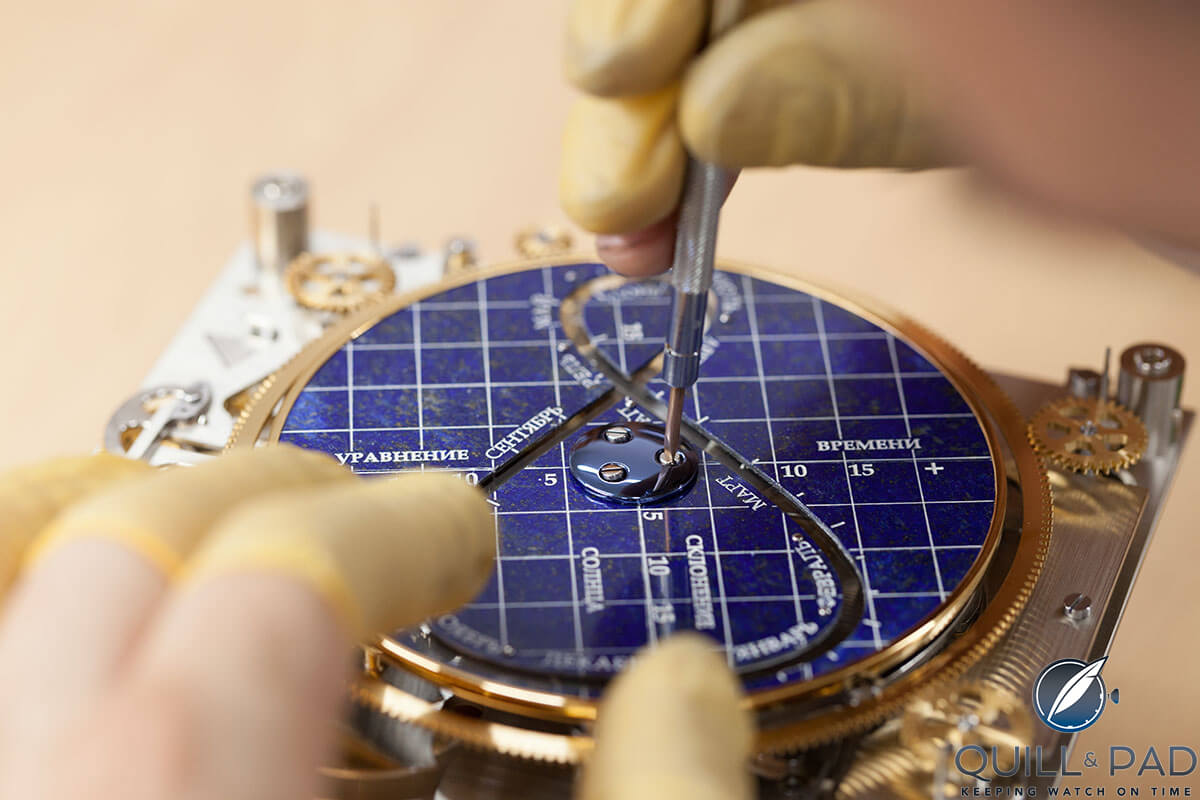

Konstantin Chaykin working on the movement of his Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

The equation of time indication is a staple of any serious astronomical timepiece, and the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock is no different. The equation of time indication is actually found on another dial, but the analemma module utilizes its own equation of time to display something else.

Due to the differences in times throughout the year and the position of the sun relative to the earth, the sun appears in different positions in the sky when observed at the same time in the same location. This results in a repeated path in the sky over the course of a year; an “analemma” is a diagram of this path.

The path ends up looking like a lopsided, squished figure eight, and the analemma module is a mechanical representation of the sun’s figure eight in the sky over the course of a year.

Analemma face of the Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

To create the motion, Chaykin uses an equation of time cam profile connected to a slider with a yellow gemstone representing the sun. This gemstone goes up and down as it rides on the equation of time cam, while the analemma dial simultaneously makes a revolution over the course of the year.

Konstantin Chaykin working on the movement of his Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

The jewel follows the path that the sun would take in a cutout on a lapis lazuli dial.

The dial is sectored to show the difference between apparent and mean solar time as well as increasing or decreasing degrees from the ecliptic. The path is also marked with the months of the year, which are divided into thirds so that a general understanding of the date could be gleaned from the display.

The sun shines over the world time display of Konstantin Chaykin’s Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

The analemma indication is also tied to four retrograde indicators in the corners of the dial that, based on the position of the sun along its path relative to the equation of time, display the times of sunrise and sunset as well as the length of day and night – accurate for one geographical location, in this case Moscow.

The astronomical information presented on this single face of the clock is pretty remarkable, representing a first in clockmaking.

Two more faces that mechanically amaze

Continuing on the clockwise journey around the Moscow Comptus Easter Clock, the next face is a mechanically visual treat with no dials (mostly) to obscure the mechanisms at work.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock: this face showcases the one-minute tourbillon at top

While it only has four indications on it (only four), it does not disappoint a mechanism nerd like me. At the top of the face is the running second indication conveniently tied to a 60-second tourbillon, providing a glimpse at the clock’s actual timekeeping.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock: this face showcases the one-minute tourbillon at top

Below this, on the right, is the sidereal indication and star chart for the sky above Moscow. This provides a real-time view of the stars in the sky whether they are visible to you or not.

Below that is the actual equation of time mechanism – well, part of it. Mounted behind a month disk, an equation of time cam rotates throughout the year while a finger rides along the profile. The finger is on the end of a lever with a rack on the opposite end that meshes with a pinion upon which is mounted the hand for the equation of time indication.

Behind the church walls of the Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

On the opposite side of the pinion a second rack meshes with the teeth, providing a force necessary for the earlier finger to remain on the cam profile. The second rack is on the end of a lever that is forced down by a steel spring.

The opposite force continually tries to push the finger into the equation of time cam, ensuring that the indication never displays an incorrect measure. The scale it points to is marked with +/-15 minutes, the maximum amounts that apparent solar time and mean solar time diverge over the year.

The layout of this mechanism is probably one of the best visual examples of an oscillating indication I have seen in practice and would perhaps be very useful in attempting to teach the basics of the equation of time mechanisms.

Movement of the Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

And speaking of great examples of mechanisms, at the bottom of this side of the clock is the winding mechanism, which represents a perfect implementation of a double ratcheting pawl wheel. This type of winding mechanism can be found on grandes sonneries and high-end manually wound watches.

Even with all the interesting and different ratcheting click designs I have seen, this still may be my favorite for its symmetry and self-contained nature.

Face four: there’s plenty more

Next up is the final face of the clock and the second new indication.

On this side we find a small earth disk centered on the North Pole that rotates once a day, enabling a 24-hour indication, while the addition of 24 slices to the dial adds the ability to tell world times (and approximate time zones) in combination with cities listed around the representation of the globe.

The earth disk is also half covered to indicate the difference between day and night (another indication). But this is nothing new. What is new comes down to the moon floating around the earth disk and its relation to the sunny gemstone at the top of the face.

This dial, while displaying world time and 24-hour indication, is actually a representation of the orbit of the moon and its effect on the phases of the moon. The earth disk rotates in the center of the dial, and the sun gemstone rests directly above it at the top. The relation between the sun and earth is static on the dial so as to show how the moon orbits the earth.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock without case

The moon is depicted with two sides: one-half is white and one-half is the dark side; the dark side always faces away from the sun. This is the side of the moon that is in shadow from the sun’s rays.

As the lunar month progresses, the moon orbits the earth counterclockwise, and from a full moon it slowly exposes more of the side in shadow to the earth until the moon is directly between the sun and the earth, and the cycle is in a new moon. It continues in its orbit and slowly exposes more of the side in sunshine until the earth is directly between the moon and the sun and we see a full moon again.

Konstantin Chaykin working on the movement of his Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

This mechanism is a first for Chaykin: it combines multiple indications into a clean and beautiful dial. The simplicity with which the complexity of the astronomical data is presented makes for a truly stunning display. But by now you should realize that even that isn’t all. Yes, there’s more!

If we continue on back to the first face of the clock we find the last visual indication: the power reserve.

Now, on its own this would be a rather standard feature. But in this case, the clock has so many indications that if the power reserve were to run out, the time spent resetting everything would not be trivial.

Because of this, a reserve alarm has been added. When the power reserve gets low enough to enter the red portion, a bell strikes to indicate that it will need to be wound again soon, and a critical power reserve indication appears in the window next to the scale.

While this isn’t a time-related alarm like a minute repeater or sonnerie, the addition of a striking mechanism tied to the power reserve is a rather cool addition to such a complicated piece.

Complicated and beautiful

The movement of the Moscow Comptus Clock is certainly complicated: it comprises 2,506 individual components, all finished to a high degree. Beveling, polishing, graining and brushing, blasting, guilloche, enamel, plating, stone setting and more are found throughout the movement, and it all combines for a rather stunning display.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

But a movement isn’t a clock until it has a case – and the case for the Moscow Comptus Clock borders on the insane.

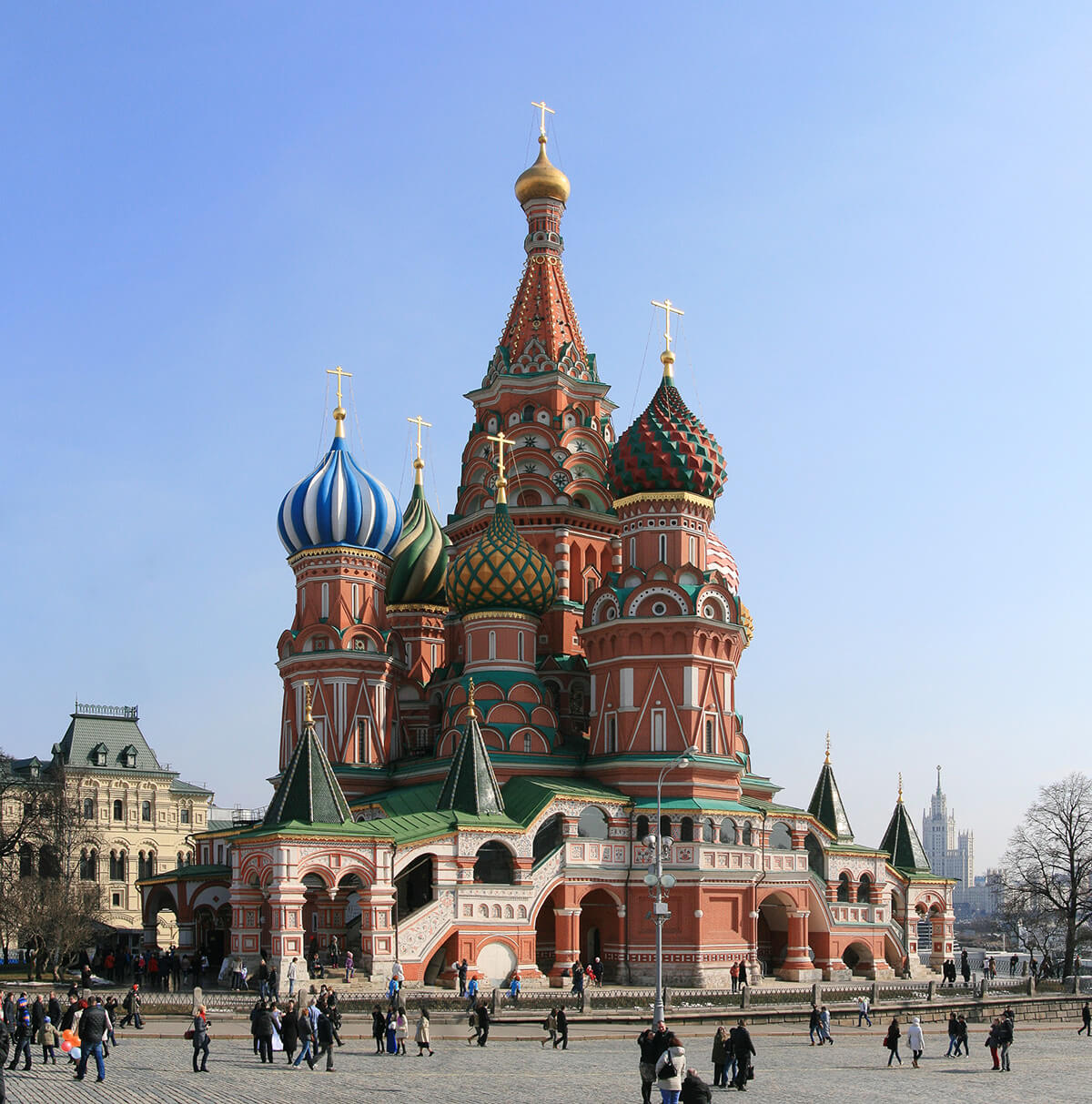

Modeled after St. Basil’s cathedral in Moscow, the case of this clock is just as complicated as the movement it houses, beginning with an aluminum-copper alloy structure supporting delicate stone marquetry.

Saint Basil’s Cathedral, Red Square, Moscow (photo courtesy Ludvig14/Wikipedia)

Then, a variety of stones were chosen to replicate the designs of the original cathedral.

A variety of pieces of yellow and green marble, jasper, jade, opal, coral, and lapis lazuli were individually cut, carved, and polished by hand to create the intricate patterns on the towers and cupolas.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

In all, roughly 2,500 pieces of stone were shaped and carefully placed to build the miniature cathedral. The process took several months as the craftsman could only complete a few pieces per day. Of the nine cupolas, eight comprise stone mosaics, while the very center one was turned from metal and plated with gold.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

The sheer intricacy of the case is astonishing, and it mirrors the horological masterpiece inside.

If this clock were to have surfaced in a Swiss or German castle, the horological world would have clapped with a familiar understanding and a superior nod because that’s where things like this show up.

Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

But considering that it was made today in the heart of Russia should be reason to exclaim. Craftsmanship and creativity abound everywhere in the world, and Russia is no exception. The inspiration of Konstantin Chaykin and his team of craftsmen is incredible and deserves to be rewarded for its fantasticness.

This amazing clock reminds me that while relations between countries might sometimes be tense, the relationship between talented craftsmen and the people who appreciate their work knows no nationalistic boundary. The incredible nature of this clock and the people behind it stand out in a world of uncertainty.

The exquisite Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

One thing is definitely certain: the Moscow Comptus Clock by Konstantin Chaykin is a highlight of the horological world.

For more information, please visit www.konstantin-chaykin.com.

Quick Facts Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock

Case: 440 x 290 x 320 mm, brass, steel, aluminum, silver, mineral glass, malachite, marble, lapis lazuli, jade, opal, coral, jasper

Movement: manually wound Caliber T03-1 with one-minute tourbillon

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; perpetual calendar with day, date, month, year, leap year, annual indication of Eastern Orthodox Easter in the Gregorian and Julian Calendars, power reserve with critical alert strike, lunar phase, star map for Moscow, sidereal time, equation of time, time of year, analemma indication, sun’s declination, sunrise/sunset times in Moscow, length of day and night in Moscow, indication of the lunar cycle relative to the solar cycle, world time

Limitation: unique piece

* This article was first published on February 5, 2017 at A Mechanical Masterpiece By A Mechanical Mastermind: The Konstantin Chaykin Moscow Comptus Easter Clock.

You may also enjoy:

Why I Bought It: Konstantin Chaykin Joker

Visiting Wunderkind Independent Watchmaker Konstantin Chaykin In Moscow (Video)

In The Face Of Complexity, Simplicity Rules: The Konstantin Chaykin Genius Temporis

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!