A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite Reviewed by Tim Mosso

by Tim Mosso

A. Lange & Söhne retains the ambiance of an independent brand. Like a maverick politician who joins a major party solely for ballot access, Lange’s existence in the Richemont collective feels more like a conduit to resources than the usual Borg-style assimilation. And the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite feels more like the type of watch that would spring from a Greubel Forsey or Lang & Heyne than from a tenant brand of the groupiest of luxury groups.

Lange has always been different. From its low volume (more than 5,000 but well under 10,000) to its management stability (a single CEO since 2011) to its surprisingly voluminous and positive employee feedback on Glassdoor.com, Lange defies expectations for an outfit extant under an imperious corporate overlord.

Interesting people have passed through its doors. The alumni club includes master independent watchmaker Richard Habring, Moritz Grossmann CEO and founder Christine Hutter; current Lang & Heyne Development Director Jens Schneider, influential watch executive Hartmut Knothe, and long-reigning Lange Director of Product Development, Anthony De Haas. These Lange shipmates and many others have had a seismic impact on the industry.

The modern version of the Lange company is a post-communist success story that started in 1990 after the fall of the wall. Strictly speaking, the collectivized GUB watch factory was the directly descended entity comprised in part of the old A. Lange & Söhne; that company today is known as Glashütte Original.

The company currently doing business under the Lange name was created by German watch executive Günter Blümlein, Lange family scion Walter Lange, and the technical team that delivered the first four production models in 1994.

A. Lange & Söhne Pour le Mérite Tourbillon

The flagship of that model line, the Tourbillon Pour le Mérite (TPLM), is the direct ancestor of today’s featured watch. With a fusée-and-chain, a tourbillon regulator, and a power reserve indicator, the fearsomely complex watch required an alliance between Lange Uhren and Audemars Piguet Renaud et Papi.

A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite on the wrist

How much and what each party contributed is a matter of which side is telling the tale, but suffice to say, the finished watch looked and felt more like a German Lange than a French-Swiss AP product.

————————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

By combining a fusée constant force device with a tourbillon regulator, Lange created a world-first that beat F.P. Journe’s conceptually similar tourbillon remontoir system to market by half a decade. In fairness, Journe’s prototype was running in 1991, but Lange won the race to market like Secretariat won at Belmont.

Not only did the TPLM set a modern-day mark for luxury horology in general, but it contributed a phrase to the lexicon of the Lange brand: “Pour le Mérite.” Originally a Prussian-conceived honor for military and later civilians, it was a prestigious accord that would have been familiar to early watchmaking members of the Lange family.

A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

2011 witnessed the arrival of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite as a model, and the white gold variant showcased herein was a 2014 update to the line. Explored from the top down, this watch reveals its magic.

“Richard Lange” is Lange-talk for “Roman numeral” dials, and we get those numerals on a dial crafted of sterling silver. While it’s tempting to describe the overlapping registers of the regulator-style dial as a “Venn diagram,” this triple-overlap “Seyffert” arrangement is named after nineteenth-century German watchmaker Johann H. Seyffert who established this style.

A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

At first glance, the one-minute tourbillon appears to be the clear star of the show, but that lasts only until roughly six o’clock. Lange watchmakers installed a trap door in the form of a partial dial that springs into view bearing the missing numerals “VIII, IX, and X.” Within the space of fifteen minutes, the sub-dial deploys to fill the gap in the hour track left by the tourbillon aperture. Once the necessary hours have elapsed, the fragment dial vanishes, leaving one’s view of the tourbillon unobstructed.

Lest it be upstaged, the tourbillon offers its own litany of tricks. Most impressive is Lange’s long-running “tourbillon hack” that permits the one-minute tourbillon to stop on command and serve as a precise second hand for the watch.

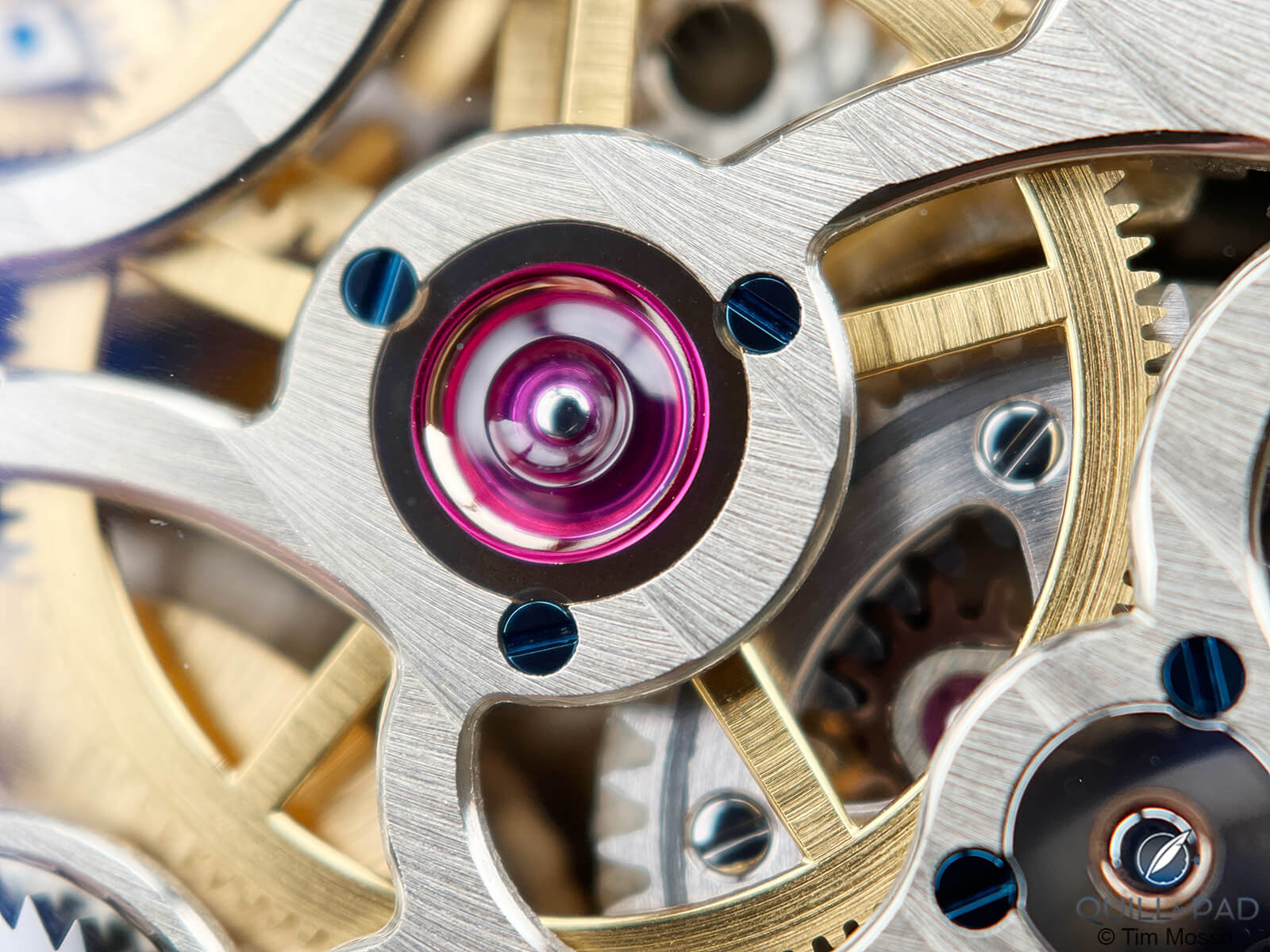

Diamond endcap on the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

At the base of the tourbillon carriage, its lower bridge features a genuine brilliant-cut diamond in place of a synthetic ruby capstone.

Naturally, an overcoil hairspring and five-position adjustment ensure that this tourbillon is as chronometrically accomplished as its aesthetics are impressive.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

The case profile of this watch is its most generic quality. There’s nothing crude or homely about the 41.9mm cylindrical vessel, its stepped lugs, or its domed bezel, but this shape suffers from overexposure. Short of the Odysseus, Cabaret, and Arkade, every modern Lange you’ve ever seen – regardless of price – has used some version of this case design. The endlessly iterated generic form is the weakest element of the RLTPLM. Even AP, for all its dress watch futility, has dared to offer more variety.

Speaking of AP, Lange does not manufacture its own cases, so the “CO” stamp on the back of this tourbillon denotes fabrication by “Centror,” an AP-connected casemaker in Meyrin. And while most Lange watches include only pin buckles, this one includes a folding clasp bearing the “BRO” signature of Monteggio-based bracelet and buckle specialist Brogioli. This explains why a German watch features Swiss precious metal hallmarks.

Back of the A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

Turn over the RLTPLM, and all is forgiven. While Lange retains the less romantic remontoir constant force device on certain models, the ancient and beguiling fusée upstages its clinical stablemate. Fundamentally, a fusée works like bicycle gearing. On a bike, you shift to a “bigger” rear gear as you climb a hill. The larger diameter gear multiplies the torque exerted by your legs to enable uphill progress. Since a mainspring loses torque as it unwinds, the fusée and chain act like bicycle gears to maintain spring force at a constant level.

Miniature chain of the constant force device on the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

The hyperboloid shape of the Lange fusée includes a spiral track that holds the .5mm thick chain while multiplying the force applied by the barrel. The fusée is attached to the drivetrain of gears that delivers torque to the escapement; it’s a constant force device that offers a constantly changing gear ratio for a constantly weakening mainspring.

Between the uppermost and lowermost gearing limits, the fusée offers infinite pull ratios. The chain binds to the fusée when the watch is wound, and it gets pulled back around the barrel as the mainspring winds down. All told, the chain is comprised of 636 pieces and would measure 15cm long if drawn out in a line.

Constant force to an escapement is a tool that a watchmaker can use to produce an outstanding timekeeper. Unwavering force to the balance wheel is a building block on which constant amplitude and a constant running rate can be constructed. Lange adds five-position adjustment and a gravity-agnostic overcoil hairspring to capitalize on the potential of the fusée. This style of layered optimization is rare in the industry for reasons of cost, complexity, and packaging challenges.

Most watches are designed to keep ideal time within a band of their mainspring torque curves rather than the entirety of it; absent real-time adjustments by a doting watchmaker, a normal watch cannot be as regular as one with a constant force system.

A particularly dramatic example of this occurred in the early 7-day IWC caliber 5000 and 50000 series movements. They tended to run too quickly when fully wound and hemorrhage time when running low. Despite upgrades through the years, this wasn’t totally resolved until the introduction of double phased mainspring torque curves of the 52000 series in 2015.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

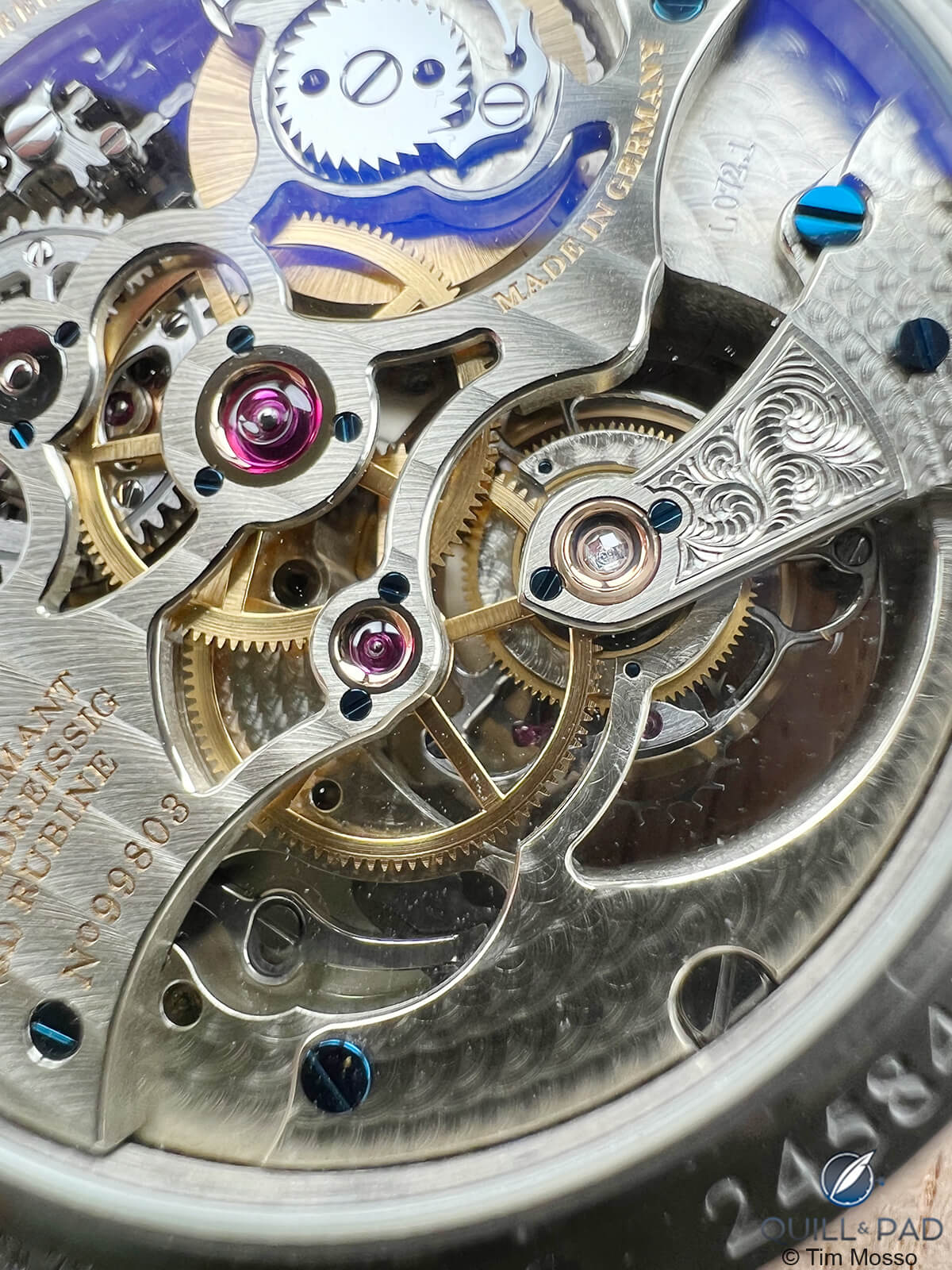

Lange casebacks are legendary – with one caveat. The vintage-inspired three-quarter bridge creates a large and dull expanse of monotonous metal where a conventional watch would reveal features like wheels, barrels, and going trains. The RLTPLM defies Lange’s own conventions with extensive skeletonization of the large mono-bridge. Caliber L072.1 reveals its fusée, chain, barrel, ratchet wheel, clicks, and drivetrain.

Beautifully hand finished movement of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

The open-wrought planetary differential inside the fusée looks the business while performing a useful function; it prevents dramatic fluctuation of the drivetrain torque when the watch is being wound.

Aside from the fusée, differential, and unconventional stop-seconds tourbillon, this Lange has a few other delightful refinements. At the conclusion of the movement’s 36-hour chronometric power reserve, a stopworks engages to halt operation rather than permit the watch to run while losing time.

Historically, watchmakers have viewed the obviousness of a stopped watch as preferable to the insidious effects of losing time while running slowly.

Another limiting system blocks excessive winding that could snap or stretch the chain. The intricate chain itself is a hand-crafted construction involving hundreds of side plates, bushings, and rivets; it’s extremely similar to a bicycle chain in miniature.

From a finishing standpoint, this tourbillon is everything one has learned to expect from a modern Lange. “German silver,” an alloy of nickel, copper, and zinc, is a pocket watch-era material that pre-dates rhodium-plated brass. This compound would have been used to fashion historical Lange watches, and its copper content imparts the distinctive pale-gold hue of the alloy.

Beautifully applied stripes on the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

Stripes – we won’t call them “côtes de Genève” on a German watch – are rich, reflective, and evenly applied.

As a side effect of the skeletonized monobridge, each window becomes a canvass for fine bevels; conventional Lange three-quarter plates have few decorative chamfers by comparison.

Hand-engraved balance cock with diamond capstone of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

The standout feature of every Lange movement is the hand-engraved balance cock. Its combination of volutes and scrolls reflects the freehand use of a burin on the tiny bridge. Since no lathe or engine is employed, the engravings on each example are unique. Lange’s use of decorative diamond capstones on tourbillon bridges is long-established but still stunning to behold.

A screw-fixed golden chaton cup holds the lower pivot of the tourbillon carriage while paying homage to the use of the same arrangement in historic watches. Although decorative today, the screw-fixed precision chaton was a necessary intermediate step in the setting of jewels before the advent of modern methods.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

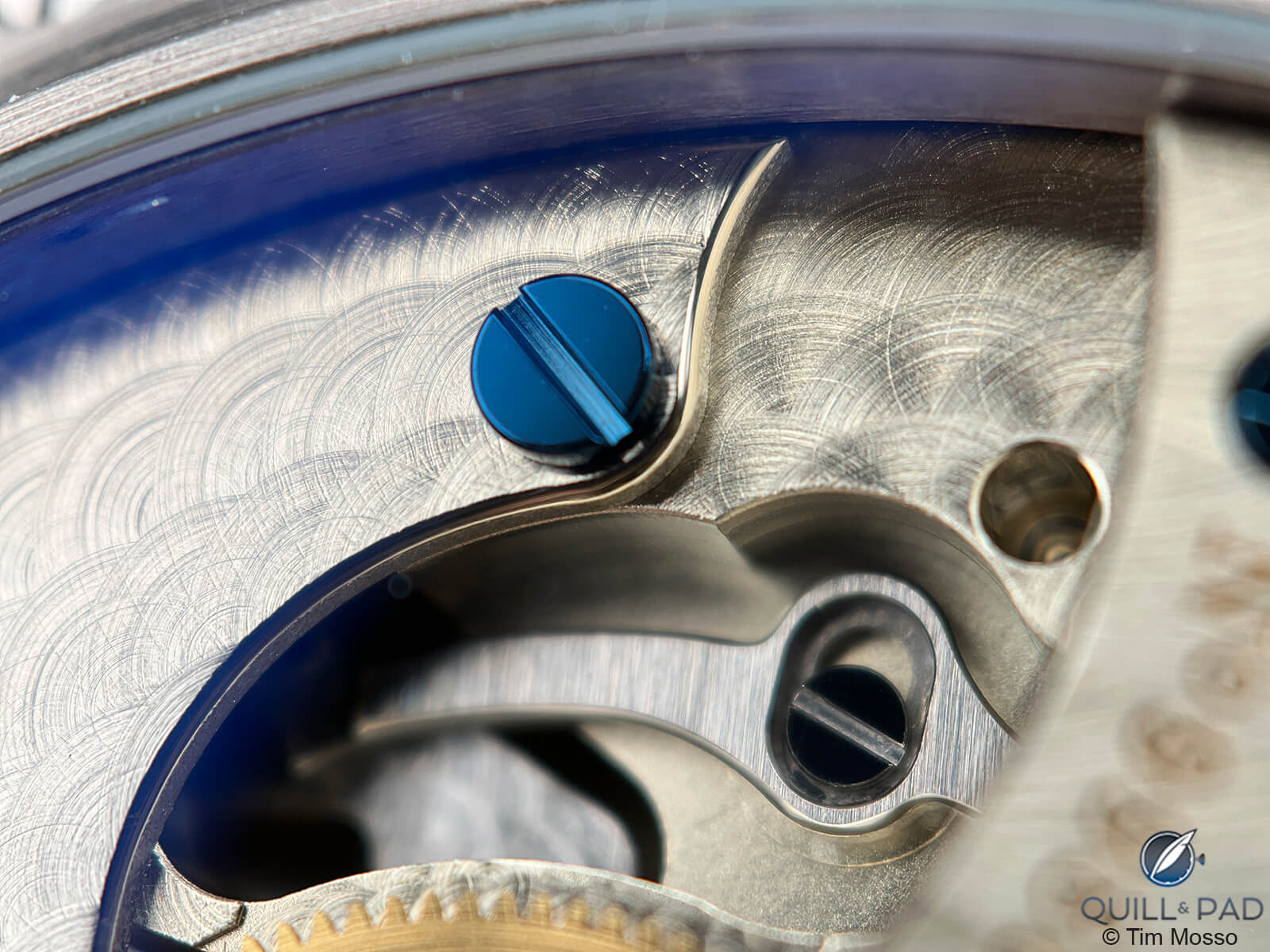

Screws are both handsome and purposeful on this caliber. All are finished with high polished heads, chamfered slots, and beveled circumferences. However, there appears to be a functional distinction between the two styles.

Polished and heat-blued screws of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

Fixed components such as bridges and jewels are associated with head-blued screws; screws associated with adjustments of spacing, tension, or timing are polished bare metal.

Lange chooses to deploy not one, not two, but three sizes of engine-turned perlage on the cascading tiers of bridges and plates. Wheels – fusée included – incorporate satin brushed metallic surfaces.

Polished gear train wheels 0f the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

However, the train wheels also sport interior bevels finished to a polished state. Although not quite on the level of the finest Greubel Forsey, this interior polishing is rare even on Swiss “holy trinity” products.

Recently, I inspected an early Philippe Dufour Simplicity, and it featured similar wheel chamfering to what I observed on the RLTPLM.

Mirror polished ratchet wheel of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

ALS watchmakers ensure a strong finish capped by a mirror-polished ratchet wheel atop a barrel blazon with sunburst graining.

Intricately shaped tourbillon carriage of the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

As a parting shot, note the shape and intricacy of the tourbillon carriage itself. The design is a direct reference to A. Lange & Söhne pocket watches manufactured before World War II. Shared history is the reason that today’s Glashütte Original tourbillon regulators employ nearly the same cage shape. On the Lange, surface polishing, micro bevels, and interior anglage of tiny recesses are virtuoso-level.

Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

Ultimately, a watch like this Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite is my “Hall & Oates” watch, because it reminds me of how out of touch I’ve become with the mainstream of the watch collector community. These white gold examples retail for $233,400 and sell used for around $140,000.

Recall that in December of 2021, somebody paid $6.5 million for a steel Nautilus with a Tiffany turquoise dial. For – far – less money, you could have a handmade masterpiece the likes of which nobody else will be wearing even if “Watches and Wonders” is on your calendar.

For more information, please visit www.alange-soehne.com/us-en/timepieces/richard-lange/richard-lange-tourbillon-pour-le-merite

Quick Facts: A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite

Reference Number: 760.026F

Case: 41.9mm diameter; 12.7mm thick; 49.1mm lug-to-lug in white gold.

Rose gold and platinum variants exist.

Dial: Sterling silver with Roman numerals, regulator with Seyffert scales, hideaway hours

Movement: L072.1, manual wind, 36-hour power reserve, stopworks, hacking seconds tourbillon, fusée and chain constant force system, retractable sub-dial, five-position adjustment, 21,600 VpH, overcoil hairspring, 31 functional synthetic rubies and 1 cosmetic diamond

Retail Price: $233,400

Preowned Market Value: $140,000-$150,000

* Tim Mosso is the media director and watch specialist at Watchbox. You can check out his very comprehensive YouTube channel at www.youtube.com/@WatchBoxStudios/videos.

You might also enjoy :

Why I Bought It: A. Lange & Söhne Pour Le Mérite Tourbillon

Happy 90th Birthday To Walter Lange With A Look Back At The Modern A. Lange & Söhne

Film: A. Lange & Söhne “A Legend Comes Home”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Die A. Lange + Söhne ist sicher eine wunderschöne Uhr. Aber mit dem Preis von 230 K. würde ich mir dann doch lieber eine Breuget aus der Classic- Linie im Bereich von 170- 240 K. kaufen. Der unterkühlte deutsche Stil, zusammen mit dem doch recht schlichten Gehäuse, fehlt meiner Meinung der Charme einer Breuget der Spitzenklasse. Für so viel Geld zählt dann auch noch die unvergleichliche Geschichte von Breuget.

Der Verglich mit einer gehypten Patek Nautilus finde ich unpassend.

Nur meine bescheidene Meinung.

Beste Grüsse

Didier

Translation

The A. Lange + Söhne is certainly a beautiful watch. But with the price of 230 K. I would rather buy a Breuget from the Classic line in the 170-240 K. range. The cool German style, together with the rather simple case, lacks the charm of a top-class Breuget in my opinion. For that much money, Breuget’s incomparable history also counts.

I find the comparison with a hyped Patek Nautilus inappropriate.

Just my humble opinion.

Best regards

Didier