Larcum Kendall And K1: The Greatest Watchmaker And Watch You Have (Probably) Never Heard Of

You may have heard of a few or more of the following historical people and events: Thomas Mudge, George Graham, John Harrison, the Longitude Prize, Captain James Cook, the First Fleet (British settling Australia), HMS Victory, Battle of Cape St. Vincent, and the mutiny on the HMS Bounty.

However, you are less likely to have heard the name of a horologist who played a pivotal role in all of the above: Larcum Kendall (1719–1790).

The first line of Larcum Kendall’s Wikipedia entry reads somewhat understatedly, “Larcum Kendall (21 September 1719 in Charlbury, Oxfordshire – 22 November 1790 in London) was a British watchmaker.”

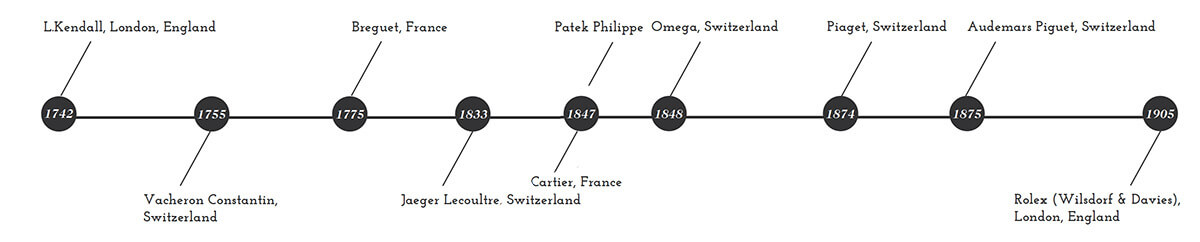

A timeline of important horological happenings (graph courtesy of Vincent Daveau, first published in ‘La Revue des Montres’ #203, April 2015)

After completing a clockmaking apprenticeship in London with the well-respected John Jeffreys, Kendall set up his own business in 1742 at No. 6 Furnival’s Inn Court, London, and over the next few decades set about making superlative chronometers that literally changed the world.

That Kendall made watches and clocks for some of the greatest horologists in history, including George Graham, Thomas Mudge (inventor of the still ubiquitous lever escapement), and John Ellicott as well as timepieces for King Ferdinand VI of Spain, bears testament to his talent.

But that was just the start.

Board of Longitude

The British Board of Longitude was set up in 1714 with the aim of finding a reliable way of determining longitude (east/west) at sea. Determining latitude (north/south) was usually done by using a sextant to measure the angle of the sun at noon, but fixing longitude was proving more difficult.

In 1765, the Board of Longitude invited Kendall to a panel of six experts who would judge a watch submitted by John Harrison for the Longitude Prize. His watch was simply called H4.

At this time, many scientists and éminences grises thought that the answer to longitude would be found in astronomy and were dismissive of “mechanical” solutions.

John Harrison’s H4 changed their world.

It’s worth noting that Kendall’s former master, John Jeffreys, had made a pocket watch for Harrison, and it was the more compact pocket watch-type marine chronometer that Harrison used in H4 that proved successful over much larger clocks (including Harrison’s own H1, H2, and H3).

Harrison spent 17 years working on H3, his third relatively large “sea clock,” but was unhappy with its precision. He was said to have been disappointed that his large clocks performed no better than some of the small pocket watches that Kendall had made for others.

So Harrison made what must have been the very painful decision to stop trying to improve H3 and instead to start working on a pocket watch-sized H4. That would take him another six years.

Harrison was 68 years old when it came time to test H4 in a round trip to Jamaica that would last just shy of three months. On its return to London 81 days later, H4 was determined to have lost just five seconds, equivalent to just one nautical mile (approximately two kilometers) of longitude.

John Harrison’s H4 marine chronometer (photo courtesy www.collections.rmg.co.uk)

H4 was so accurate that the Board of Longitude thought it might be a lucky fluke and asked for another test voyage, which the marine chronometer similarly passed with flying colors.

The movement of John Harrison’s H4; we can assume Larcum Kendall’s K1 looked very similar (photo courtesy www.mikepeel.net)

Harrison was 80 years old before the Board of Longitude finally recognized that he had won the prize, and even that was only after Harrison had petitioned King George.

Kendall’s K1

The Board of Longitude then asked Kendall to make a copy of Harrison’s H4, for which they would pay £450. That watch would become K1.

K1 was presented to the Board in 1770 and Kendall was paid the agreed £450 plus another £50 for additional fine adjusting as well as servicing Harrison’s H4, which was also now owned by the admiralty.

Larcum Kendall’s reproduction of Harrison’s H4 marine chronometer called K1; judging from the dial side, it’s an excellent reproduction (photo courtesy www.collections.rmg.co.uk)

To put that price in some perspective, the British navy paid £1,800 to buy HMS Resolution, a ship the size and quality needed for one of the British navy’s most respected officers and one of history’s best navigators, Captain James Cook, to travel the globe for years – much of it to territories completely unknown to European nations at the time.

‘HMS Resolution,’ the ship that Captain James Cook used to explore the South Pacific and sail the globe

This was a serious geopolitical business for Britain; the stakes were high.

Cook’s second voyage of discovery, 1772–1775

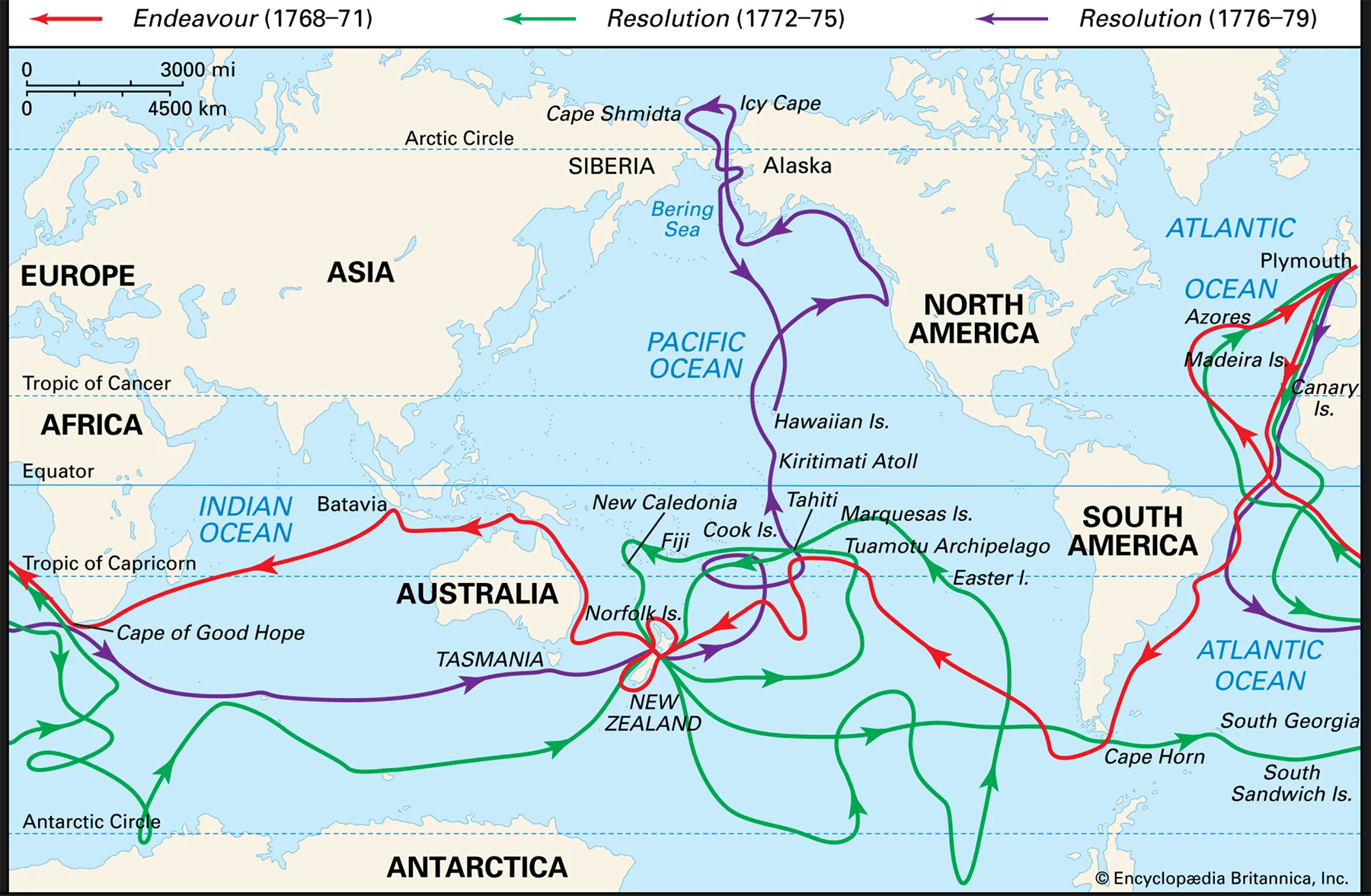

Captain James Cook tested K1 on Cook’s second South Seas journey on HMS Resolution (1772–1775) with William Wales (astronomer).

James Cook’s three Pacific voyages (image courtesy Britannica)

While initially skeptical, Cook reported to the admiralty that, “Kendall’s watch has exceeded the expectations of its most zealous advocate.” He also described K1 in his log as, “our trusty friend the Watch” and “our never-failing guide the Watch.”

This proved to the somewhat still doubting scientific establishment that H4’s performance was no lucky fluke. And K1’s reliability was highlighted by the fact that there were also three marine chronometers by John Arnold on the voyage that had all stopped working.

Cook’s third voyage of discovery, 1776–1780, and more

Cook took K1 on his third voyage to the Pacific, again on HMS Resolution (1776–1780). And again the chronometer exceeded expectations.

However, in June 1779 the balance staff was broken and K1 was returned to Kendall for repair. Once fixed, K1 left England on HMS Sirius, which was part of the First Fleet heading out to settle Australia (as a penal colony).

K1 arrived at Botany Bay (Sydney) in January 1788 and after being used by astronomer William Dawes for a few months on land, joined HMS Sirius again on a trip to Cape Town in South Africa to collect supplies for the new colony (basically a trip to the shops).

K1 eventually returned England in April 1792.

The following year, after a service interval that many watch brands still have trouble bettering today, K1 headed out to the West Indies with Admiral Sir John Jervis. After the Caribbean, K1 sailed to the Mediterranean and was on board HMS Victory at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, which took place between the English and the Spanish off Portugal.

K1 was described by John Gilbert, master of the HMS Resolution on Cook’s second voyage as, “The greatest piece of mechanism the world has ever seen.”

K2 and the mutiny on the Bounty

In 1772, Kendall created K2 with the aim of making a more “affordable” precision chronometer around half the price of K1.

While not quite as good as K1, K2 first sailed in search of a northwest passage above North America and then on to warmer climes in 1787 in the Pacific Ocean with Captain William Bligh on the HMS Bounty.

In 1789, the infamous mutineers took both HMS Bounty and K2, and the latter disappeared until . . .

. . . 1808, when an American ship rediscovered Pitcairn Island, where some of the mutineers had settled. John Adams, the last surviving mutineer, then gave K2 to the ship’s captain, Mayhew Folger.

Larcum Kendall’s K2 marine chronometer (image courtesy www.prints.rmg.co.uk)

Folger then sailed to Juan Fernandez Island off the coast of Chile, where the Spanish Governor confiscated K2. It was then bought by a Spaniard called Castillo. When he died, his family gave K2 to a Captain Herbert of HMS Calliope, which sailed from Chile back to England in 1840. Herbert then bequeathed K2 to the British Museum.

Both K1 and K2 are now kept at the British National Maritime Museum, in Greenwich, England.

Few, if any, watchmakers in history have had such an impact on world events as Larcum Kendall, even if we are now fully unaware of it.

His life illustrates just how fundamental to our lives precision timekeeping once was. And very much still is.

The reason this giant of horological history is relatively unknown is because Larcum Kendall was a superlative craftsman rather than an inventor, with his best works being the execution of creations imagined by other great watchmakers. Kendall was the epitome of the “watchmaker’s watchmaker,” and the world we know today would not be same without his impressive contributions.

For more information, please see the Greenwich museum’s website at www.collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/79143 and you might also enjoy reading Books on chronometer trials (RGO 4/312) as much as I did.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] McEvoy: On the Bench with Larcum Kendall’s K1 (for more on Kendall see Larcum Kendall And K1: The Greatest Watchmaker And Watch You Have (Probably) Never Heard Of) James Dowling: Wristwatch Navigation, from Weems to the Mark 11 Kurt Brøndum: Collecting […]

-

[…] *This article was first published on June 8, 2016 at Larcum Kendall And K1: The Greatest Watchmaker And Watch You Have (Probably) Never Heard Of. […]

-

[…] dovetailed settings are a strange and awkward arrangement for jeweling, and Larcum Kendall (see Larcum Kendell And K1: The Greatest Watchmaker And Watch You Have (Probably) Never Heard Of) abandoned this in his K1 copy, using instead conventional settings and endpieces held in place by […]

-

[…] dieser witzigen Beschreibung ticken zwei Uhren um die Wette, die eine ist von Larcum Kendall, die andere von John Arnold (zwei weitere Uhren von Arnold werden auf Cooks Reise ihren Geist […]

-

[…] Quill and Pen: Larcum Kendall and K1: The Greatest Watchmaker and Watch You Have (Probably) Never Heard Of […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

What a marvellous article – thanks so much for writing this!

One can’t help wondering what it would take (cost) for someone to create a facsimile of K1 today?

I’m glad to hear that a few people liked the article, Gerald.

Derek Pratt was working on a reproduction of Harrison’s H4 but unfortunately died before it was finished. I understand that Frodshams in London has taken over the project but haven’t heard news in years. Your comment has encouraged me to chase that up.

Regards, Ian

Hi Ian,

The Pratt/Frodsham “Harrison” was magnificently completed in 2014, and was one of the highlights of the exhibition “Ships, Clocks & Stars” that started at the National Maritime Museum, and which has also travelled to USA and Australia. We ran a series of articles in The Horological Journal about some details of this amazing timepiece, including details on the making of replicas of Harrison’s diamond escapement pallets, something that’s confounded scholars of practical horology for centuries! I can help you with electronic copies of this if you’re interested.

All the best,

I am very interested thank you Justin and will be in touch.

Regards, Ian

What a great piece. The intersection of watches and history, especially marine history and aviation history, is always fascinating and to see one watch go through that much history itself is fantastic

-Amateur Horologist

Check out https://amateurhorologist.wordpress.com/

Great article! Keep up the amazing work!

I really enjoyed this article; overwhelmed and informative.

Nice article Ian!

You might be interested to know that Derek Pratt’s H4 copy was finished in recentl years and is on display at the NMM’s exhibition Ships, Clocks and Stars, currently at ANMM Sydney. It sits alongside all of Kendall’s copies and Harrison’s H4.

Thank you very much for that news, Rory, it sounds like it is time for me to visit Greenwich again.

Call me a hipster but I love pocket watches, they’re absolutely gorgeous!

In the account I have just read (by Bengt Danielson), Ian, Folger was met by three youths in a canoe claiming to be the sons of “Alec” – i.e. Alexander Smith, the only surviving mutineer.

Perhaps we are related…

That would be a good family story Colin.

The map shows Cook’s first voyage, not second.

Thank Bob, that now been corrected.

Regards, Ian