The 2017 Gaïa Awards: Richard Mille, Jean-Marc Wiederrecht, And Laurence Marti Honored

In 1993, the Musée International d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds (MIH) created the Prix Gaïa to honor the memory of one of the earliest patrons of the museum, Maurice Ditisheim.

In sharp contrast to the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève, which can be seen more as the Academy Awards or Oscars, the Gaïa has often been called the Nobel Prize of the watch industry.

Craftsmanship, creation: Jean-Marc Wiederrecht

The jury of the 2017 Prix Gaïa awarded Agenhor founder Jean-Marc Wiederrecht “for his creative contribution to horological complications, marrying function with beauty in his work for many brands.”

Jean-Marc Wiederrecht (left) with Singer Reimagined founders Rob Dickinson and Marco Borraccino

My own take on Wiederrecht’s attitude toward the mechanical watch is that it is rather poetic. One of the true mechanical artists of the luxury watch industry, Wiederrecht seems to me to be chiefly occupied with the purest values of this art form. And those are rare attributes – and even rarer when you stop to consider that he has been able to build a thriving business on such values.

Wiederrecht finished his watchmaker education at Geneva’s school of watchmaking in 1972, beginning his career at the height of the quartz crisis. Perhaps this is why he has adapted such a modest outlook on life, growing up with an industry that had to re-learn the values and luxury of the mechanical watch. He first worked for Châtelain, then set up his own business in 1978.

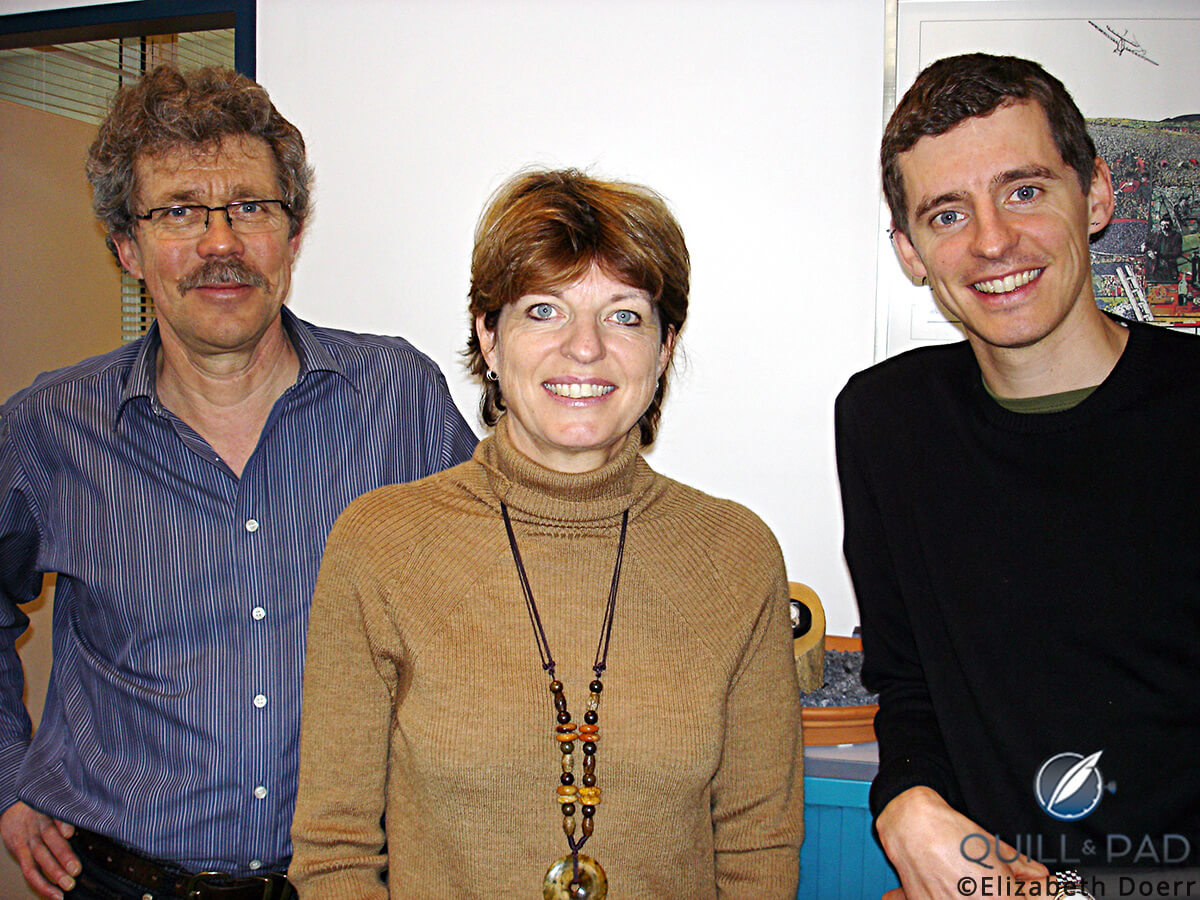

Jean-Marc Wiederrecht (left) with his wife Catherine and son Nicolas; Agenhor is a family business

Wiederrecht and his wife Catherine founded Agenhor SA in 1996. Their business is a custom one, boasting an impressive catalogue of some of the world’s most complicated timepieces – watches that he and his team developed for his clients, including perpetual calendars, jump hours, retrograde functions, and spatial mastery.

Wiederrecht patented his perpetual calendar retrograde complication in 1988, which he developed with Roger Dubuis. Simplicity is key for Wiederrecht, and he relies on his instincts, not a paper trail or virtual realities to create timepieces for his many clients. “One of the problems [of our industry] is that you can make what you want with the computer; virtual watches have exploded,” Wiederrecht once explained his philosophy to me. “When I make something, it is very simple. If it is too complicated, you can forget it because it won’t work.”

Now 67 years old, Wiederrecht has laid the future of Agenhor primarily in the hands of his two sons, Laurent and Nicolas, as he and Catherine have decided to at least partially retire and enjoy the beauty of the wider world, something that has always drawn the philosophically inclined Wiederrecht.

Van Cleef & Arpels Le Pont des Amoureux in collaboration with Agenhor

Some of the key watches Wiederrecht and his team at Agenhor have created include Harry Winston’s bi-retrograde perpetual calendar, MB&F Horological Machine No. 2, the Arnold & Son True North, Harry Winston Opus 9 (see The Harry Winston Opus Series: A Complete Overview From Opus 1 Through Opus 13), Van Cleef & Arpels’s Poetic Complications, the Hermès Arceau Temps Suspendu and Slim d’Hermès perpetual calendar and L’Heure Impatiente, the Fabergé Visionnaire DTZ, and the AgenGraphe, which now powers the Fabergé Visionnaire Chronograph and the Singer Reimagined Track 1.

Fabergé Lady Compliquée Peacock by Agenhor

In 2007, the unassuming watchmaker won one of the industry’s highest honors: Best Watchmaker at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève. Wiederrecht received his award to thunderous applause from the audience, which comprised key figures of the watch industry. “It was completely crazy,” the modest Wiederrecht once remembered with a smile when I asked him about it. “One thing I remember very strongly when my name was called was that a lot of people applauded a lot. And that was a very big surprise: I didn’t know I was so well known at the time.”

In winning the 2017 Prix Gaïa for Artisanal Creation, Wiederrecht joins technical and artistic virtuosos that include the likes of François-Paul Journe, Michel Parmigiani, Derek Pratt (who co-created many Urban Jürgensen recent-history works), George Daniels, Beat Haldimann, Swatch’s Jacques Müller and Elmar Mock, Corum’s René Bannwart, automaton maker François Junod, Eric Coudray of Cabestan and Jaeger-LeCoultre, and A.H.C.I. members Vincent Calabrese, Philippe Dufour, Paul Gerber, Andreas Strehler, Vianney Halter (last year’s winner), and Kari Voutilainen in this category. Anita Porchet has been the only female recipient thus far (see The 2015 Gaïa Awards: Giulio Papi, Anita Porchet, And Jonathan Betts Honored).

Entrepreneurship: Richard Mille

The jury of the 2017 Prix Gaïa awarded Richard Mille “for the leading role played by his business in defining modern luxury Swiss watchmaking on a global scale and his bold and innovative use of original materials and development of futuristic creations.”

Mr. Richard Mille at the opening of the Richard Mille boutique in Munich, Germany (photo courtesy Michele Mussler)

Now 66 years old, French-born Mille has spent most of his professional life in the watch industry though he was never formally schooled in design or watchmaking, but has mainly been involved in the management side of operations. However, there lurked within him a myriad of ideas just waiting to spill out and in 1999, he took the plunge, in 2001 launching his now iconic eponymous brand.

When I asked him early on in his career, Mille likened his feel for high-end watchmaking to Enzo Ferrari’s automobile genius. The legendary Italian carmaker, also a frustrated manager who ended up founding his own brand though he was not an engineer or designer, was in a similar situation back in the 1930s.

Richard Mille at the wheel of his 1967 BRM at the 2015 Richard Mille Chantilly Arts and Elegance

An enthusiastic and passionate man – Mille not only loves watches, but also technology and car racing – in 2001 he felt it was time to express those interests concretely by making his wristwatches into micro machines that look as if they could turn on their booster rockets any minute and take off from the wrist, almost like a Formula 1 racing car. In fact, Mille gets much of his inspiration from Formula 1.

Audemars Piguet’s Renaud et Papi (APRP) worked with Mille from the start thanks to a previous association during Mille’s time as president of Mauboussin. Vaucher was also one of his early suppliers thanks to its willingness to experiment with titanium in movements, something not done before Mille.

“Generally speaking, I have an idea in my head, and then I try to find people who can find out if such an idea is possible to physically realize and create. If you want to do things out of the ordinary, then you have to tap into the technical know-how around you,” Mille told me back in his early days of independent creation.

“I am open to any and all ideas, talk with everyone, and shut nothing out! But sometimes I am too far ahead and have to wait a few years for some ideas to come to fruition, because they are too difficult. Happily, I have so many ideas that this is not a major problem,” Mille explained.

Richard Mille RM 11-02 Automatic Flyback Chronograph Dual Time Zone Jet Black

Today, he often looks outside the watch industry for supplies and suppliers, his creative company now able to produce a great deal more of its own elements like cases and movements. Focus has always been on ultra-light materials and the ability of his watches to stand up to the grueling torture that professional athletes put them through. Anticorodal 100, alusic, TPT Quartz, and graphene are just a few of the materials in the Richard Mille arsenal of science-fiction-like materials.

In winning the 2017 Prix Gaïa for Entrepreneurship, Mille joins a list of visionary laureates that read like a who’s who of Swiss watchmaking: Günter Blümlein (A. Lange & Söhne), Luigi Macaluso (Girard-Perregaux), Rolf Schnyder (Ulysse Nardin), Nicolas G. Hayek (Swatch Group), Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey, Jean-Claude Biver (Blancpain, Hublot), Philippe Stern (Patek Philippe), Franco Cologni (Cartier, FHH), Ernst Thomke (Swatch Group), and Giulio Papi are just a few of these illustrious names (see The 2015 Gaïa Awards: Giulio Papi, Anita Porchet, And Jonathan Betts Honored).

History and Research: Laurence Marti

The jury of the 2017 Prix Gaïa awarded Laurence Marti the prize for History and Research “for the major contribution to our knowledge of the social history of watchmaking through her handling of original sources and for the spirit of independence, which she fully embodies.”

Laurence Marti, winner of the 2017 Prix Gaïa for History and Research

Born in Bévilard, Switzerland, Marti studied sociology and history at the Universities of Lausanne and Lyon. After earning her doctorate she opened a private research office in Aubonne (near Geneva) to make her scientific skills available to businesses, institutions, associations, museums, and individuals for research projects, preparing exhibitions, and creating commemorative works.

She helped create the Centre Jurassien d’Archives et de Recherches Économiques (CEJARE, the Jura Archive and Economic Research Centre) in Saint-Imier in 2001, which she led until 2008.

Alongside her role as president of the Jura Archives Foundation (le Conseil de Fondation de Mémoires d’Ici), the center for research and documentation of the Bernese Jura in Saint-Imier, Marti also plays an active part in several other organizations. In 2011, she was awarded a distinction by the Council of the Bernese Jura in recognition of her outstanding work in the field of culture. She has published a multitude of papers, articles, and books on the subject of watchmaking a historical and socio-cultural contexts.

Marti joins past winners Roger Smith, Jonathan Betts, Henry Louis Belmont, François Mercier, Ludwig Oechslin, Jean-Luc Mayaud, Jean-Claude Sabrier, Yves Droz, Joseph Flores, Estelle Fallet, Kathleen Pritschard, Catherine Cardinal, John H. Leopold, Pierre-Yves Donzé, Francesco Garufo, Günther Oestmann, and Pierre Thomann as a laureate in this category.

For more information on the Prix Gaïa, please visit www.chaux-de-fonds.ch/musees/mih/prix-gaia.

You may also enjoy:

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!