To this day, when most people think about luxury watches they picture a little white-haired man in a white lab coat bent over a workbench against the backdrop of snowy Alps busily filing away at watch parts.

It’s a lovely picture, but not very representative of the modern – or even necessarily traditional – watch industry. While that picturesque watchmaker may have existed 200 or 300 years ago, chances are that he was not making an entire watch, but rather specialized components for one.

The archetypal image of a watchmaker: Philippe Dufour at work

The watch industry was – and in large part remains – predominately a cottage industry, which means that watchmakers were generally specialized in one component, a set of components, or in assembling components. Our wizened, white-haired watchmaker would then deliver his components, along with dozens of other suppliers, to another specialist practiced in assembling them into to one ticking whole for a “brand.”

This process has radically changed over the last ten years or so thanks chiefly to the modern importance put upon the term manufacture (in this sense meaning made in-house by a brand). The melding of companies – including takeovers and mergers – that has occurred over the last two decades has resulted in consolidation and blurred lines, at least for the big-name brands. But also behind the scenes among suppliers, which continue to change hands and become integrated into a larger whole.

Revolutionary changes: CAD, CAM, and CNC

For centuries all watch parts were made by hand using traditional tools and hand-driven lathes because that was all that was available; however the last 15 years have brought about revolutionary changes in how a mechanical watch is manufactured.

One of the catalysts has been CAD/CAM designing tools for the computer, while CNC and other computer-controlled machinery such as wire spark erosion (EDM), which allows for more precision in manufacturing individual components, has driven the move to manufacturing processes that can no longer be described as accomplished “by hand.”

Base plates, bridges, levers, and other flat parts are quickly and precisely made by numerically controlled machinery (CNC), which makes one of the biggest challenges today the efficient programming of the machines. This is why today we can say that flat parts are generally manufactured by engineers and programmers rather than trained watchmakers.

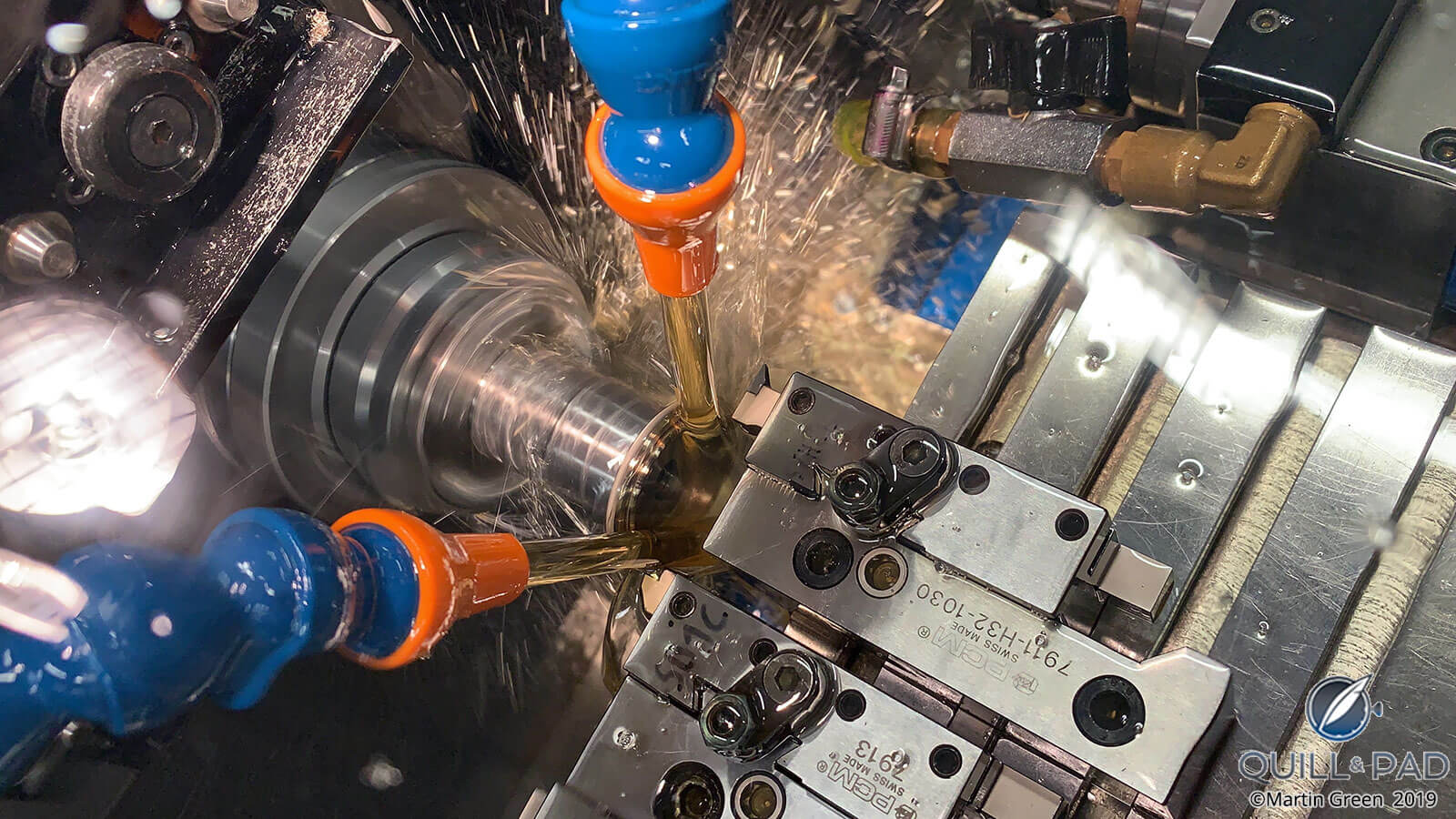

A CNC machine making a watch case at Les Artisans Boîtiers

For example, when I visited Roger Smith’s little workshop on the Isle of Man back in 2008, he employed five technicians: four watchmakers and one engineer to run the then brand-new CNC machine.

In 2011, when Tutima officially opened its Glashütte manufactory, one of the 15 technicians working there was a CNC operator who came from outside the watch industry and was described by the brand’s production head at the time as “a most creative engineer.” His problem-solving ability allowed the small manufacture to work with smaller tolerances and end up with better results for the brand’s minute repeater.

The same can be said for turned parts such as pinions, pivots, and stems. These minuscule components are generally crafted in hardened steel and turned on a lathe. Automatic computer controlled long lathes are programmed to draw the steel tubes, cut them into the proper lengths, and turn and thread them appropriately. They are run by operators rather than watchmakers, so that the machines tirelessly work both day and night. These parts, too, are no longer generally made by hand.

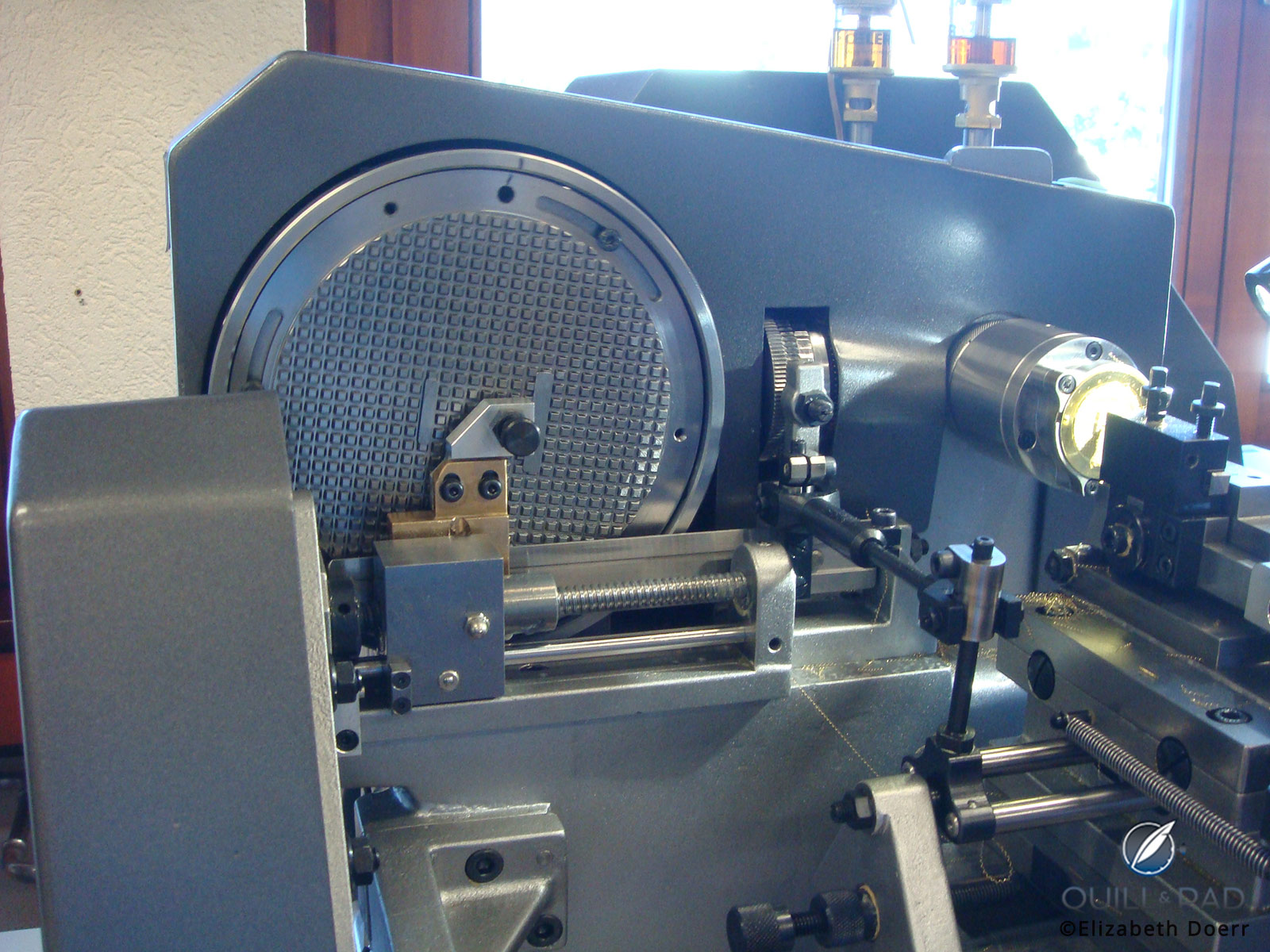

A few of the high-precision long lathes at Elwin

Another important catalyst removing the industry at large from being “handmade” was the world of new materials. These include nickel-phosphorous LIGA components and Mimotec’s easy access to the technology – which allowed for components with extremely high precision and often not requiring lubrication.

LIGA was closely followed by silicon technology. Silicon is revolutionizing escapements (and balance springs), allowing for much higher frequencies since neither wear nor lubrication is an issue.

Watchmaker Martin Braun once explained this point to me very succinctly. “For years, I had thought about improving the standard Swiss lever escapement for my own movements. What I was envisioning was simply not possible with conventional materials and production methods. It was the advent of silicium [silicon] for watchmaking that allowed me to finally realize the solution I imagined.”

In short, this had to do with the Swiss lever escapement’s geometrical angles, which in his opinion have represented a compromise between effectivity and the capillary effect (which keeps oil in its proper place). “This no longer needs to be adhered to since an escapement predominately comprising silicium components can function without oil,” he commented. Braun did eventually launch a perpetual calendar movement containing a silicon escapement before the unfortunate demise of his boutique brand, Antoine Martin.

The perceived ideal: George Daniels and Philippe Dufour

What that imaginary little watchmaker in his time-honored atelier has lived off in recent history is doubtlessly more widespread news of late independent watchmaker George Daniels’ workshop. In his early days Daniels restored and curated antique pieces for Sotheby’s auction house and later notably made only a handful of timepieces by hand. He didn’t work much differently in the final moments of his active career than he did at the beginning of it.

Daniels’ workshop displayed a visible love of his craft and the traditional execution of it, filled with what would today be considered vintage tools and treasures possibly found at auction or second-hand markets.

George Daniels demonstrating a technique in his Isle of Man workshop, 2008

Philippe Dufour, who still actively produces watches, comes as close these days to the imagined ideal making handmade watches. Dufour, it should be said however, receives his base plates from a supplier who manufactures them by CNC – and other components as well.

Nonetheless, Dufour spends much more time and effort on the handcrafted parts of his watches than just about anyone else: handmaking parts he cannot get supplied, filing and perfecting those that are supplied, and above all finishing every piece by hand in his fastidious way.

The few watches that emerge from Dufour’s workshop every year are indeed about as close to handmade as the watch industry is capable of producing in this day and age now that Daniels is gone.

“[Today’s companies] are not seeing the big picture; the handmade watch has much more elegance – like nature, it is proportional. It is important to make it flow, otherwise it is just a box of gears,” Daniels told me a few years before his death.

And like Dufour, Daniels put particular emphasis on finishing. “Finish reflects perfection,” he said, echoing Dufour’s unspoken sentiments.

A newer entry, Greubel Forsey is both renowned for its high-end hand-finishing and the importance of preserving traditional handmade skills and techniques. This is epitomized by the brand’s Hand Made 1.

Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1: note the ‘hand made’ in place of ‘Swiss made’

It’s all in the finish

The finishing is therefore what we are usually referring to in modern “handmade” watches since most mechanical watches are assembled by hand. And here is where the lines really do blur and the consumer can be easily confused.

Many traditional movement decorations and finishes that were the mark of the finest timepieces can be reproduced today by automatic or semi-automatic machinery.

Some of the rose engine guilloche team at the Breguet manufacture

Guilloche, for example, is the broad term used by every watch company under the sun for the geometric patterns cut into a dial or on flat movement parts such as rotors. While guilloche was historically made using rose engines and straight cutters powered by crank or foot pedal, today the term often encompasses machine stamping and the use of pantograph – an automatic “tracing” system using a “finger” to transmit a pattern from a large template to a graver that engraves a small component.

A pantograph at Audemars Piguet used to produce Tapisserie dials

The price of the watch will generally determine the type of guilloche, though not always: Audemars Piguet and Ulysse Nardin often use pantographs to produce their luxurious dials.

Because of the time and skill involved in applying it, authentic guilloche is usually only found on limited quantity watches, such as those from Roger Smith’s workshop, Patek Philippe (who employs a lone craftsman), and other small, exclusive, and mainly independent companies.

Breguet is doubtless the largest producer of handmade guilloche with its own facilities, dozens of rose engines both new and old, and even a guilloche training center in the heart of Switzerland’s Vallée de Joux.

There are few suppliers left – such as Jochen Benzinger in Pforzheim, Germany, and some high-end dial makers in Switzerland – capable of producing this almost lost art.

The high art of watchmaking includes real hand finishing

Hand-finishing goes beyond guilloche and engraving, and Giulio Papi, head of Audemars Piguet Renaud et Papi (APRP), has been an adamant proponent in helping consumers to understand the difference between an “industrial” finish and a movement that has been completely finished by hand. To Papi and others at Audemars Piguet, this is a big part of the art of high watchmaking.

Giulio Papi

According to Papi, it is beveling that reveals the handmade quality of a wristwatch. “The expert eye will be able to recognize this as such by identifying the technique that has been used,” Papi has said.

Beveling is a meticulous finish that contributes to the mechanical beauty of the movement by breaking the light, which adds an extra shine. It removes hard edges and any nicks and scratches that may have occurred during the manufacturing process while remaining perfectly regular at a consistent (usually around) 45-degree angle. “It exalts the authenticity of the horological art,” says Papi.

This sort of precision and beauty goes for all hand-finishing polishes and cuts, which include côtes de Genève, perlage (also known as engine turning), sunray and other styles of brush polish, and all fine finishing of every single part, including drilled holes and even in between the teeth of a pinion.

Watches of the mid-priced segment and below have machine-applied finishes (if they have any at all). From mid-level on up, finishes may be partially machine applied – complication suppliers such as Dubois Dépraz and La Joux-Perret, for example, utilize machines that automatically apply perlage and Geneva waves.

As a rule, high-end luxury watches all bear hand finishing with the finest examples perhaps achieved by Greubel Forsey, A. Lange & Söhne, Vacheron Constantin, Kari Voutilainen, Breguet, Romain Gauthier, and – of course – Philippe Dufour.

Philippe Dufour producing his painstaking finish

“A high-end watch takes an above-average amount of time to create,” says Papi. And this is precisely what makes the difference in the end: it is the amount of time, energy, and traditional expertise put into a watch that differentiates the handcrafted from an industrial-level timepiece. And in most cases, it will also be the difference between a $5,000 watch and those costing much, much more.

* This article was first published on July 29, 2020 at What Defines A Handmade Mechanical Watch In The Modern World?

You may also enjoy:

Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1: Making A Watch The Traditional Way (Video)

How It’s Made: Inside The Breguet Castle Of Complications

Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1: Hands Breathing Life Into Metal

Silicon: A Closer Look At The Material That Unleashed A Refreshing Range Of Haute Horlogerie Ideas

RGM Watch Company: American In-House Manufacturing Case Study

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

There are a handful of independent watchmakers now that have gone the extra step- crafting base plates, screws and cases by hand (no CNC). Everything except crystal, jewels, and hairspring.