The Diving Bezel: The Most Versatile Watch ‘Complication,’ Even If You’re Not A Diver

I’m all about how to best spend my time. And I like to spend it underwater – a place where minutes can mean the difference between life and death. Contrary to high altitudes, the ocean depths are open to everyone and have become a popular playground for today’s adventurers.

Dietmar W. Fuchs wearing his Blancpain Fifty Fathoms (photo courtesy Aaron Wong)

Just a glance at a diver’s watch bezel instills confidence that this timepiece is ready to take on all adventures.

But what exactly is a diving bezel? What’s the difference to other bezels that look similar, or even the same, but are not suitable for diving? And aside from diving, on what other great adventures can the diver’s watch be a valuable partner?

The versatility of the bezel on a diver’s watch

History of the diving bezel

In 1943 engineer Émile Gagnan and navy diver Jacques-Yves Cousteau invented the Aqua-Lung, a diving regulator supplying compressed air under variable pressure conditions.

The Aqua-Lung revolutionized diving, as previously divers had to use either cumbersome equipment connected by a hose to the surface or a pure oxygen breathing apparatus (rebreather), which could become toxic at greater depths.

The invention of SCUBA (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) equipment made diving to much greater depths both safer and easier.

The dawn of sport diving

Unfortunately, many divers at that time lost their lives or health due to nitrogen narcosis caused by breathing highly compressed air over an extended time. Scuba divers required two important instruments to safely perform a successful dive: a depth gauge and a dive timer.

Original Blancpain Fifty Fathoms from 1953

Depth gauges and dive timers had be accurate and reliable, and the diver needed to be skilled at reading and calculating numbers under pressure. If either depth or time limits were exceeded it was all too easy to get severe decompression sickness and even die.

Depth gauges were available as of World War II, as were some water-resistant watches. But still accidents happened until it was discovered that our brains do not work properly if immersed under pressure for a longer time (which brings me to the helium valve, but that’s a story for another day).

So inventive divers got the idea to use pilot’s watches, which had a special bezel to mark time – but accidents still happened.

Jean-Jacques Fiechter in his natural habitat

Until one smart Swiss diver, Jean-Jacques Fiechter, then CEO of Blancpain, had the idea to either fix the bezel so it cannot be moved accidently or limit it to just counterclockwise movement, which in the worst case would indicate a longer dive time, thereby shortening the dive (which I dislike, but not as much as getting the bends).

Fiechter discussed this idea with a captain of the French navy who was looking for a reliable, tough instrument to accompany his newly formed combat diver unit, and together they invented the first modern diver’s watch, one that could be used at greater depths and with a reliable safety feature. And it was perfect for scuba diving!

How to set dive time

Most sport divers set the reference marker (a triangle of some sort on most watches) to the minute hand at the time they enter the water and begin diving. From that moment, the dive time (in minutes) can be checked on the bezel, while depth is controlled on a separate pressure gauge.

Setting dive time using the bezel’s reference marker

But how does the diver know when to end the dive?

In the early 1950s there was no instrument available to calculate decompression times. But decompression tables were quickly developed to check no-decompression time – the time when a diver should resurface without having to make a decompression stop under water.

Experienced divers (especially those who weren’t too excited about all these numbers) devised an easy rule to calculate decompression time in the head: the 90s rule.

The 90s rule

If you double the maximum depth and subtract the result from 90 you get your no-decompression time.

Here is an example using a maximum depth of 25 meters: doubled makes 50, subtracted from 90 gives you 40. That’s 40 minutes of no-decompression time at 25 meters.

At 30 meters it’s 30 minutes, at 40 meters 10, and unfortunately at 50 meters the formula no longer works, necessitating tables. I’ll follow up on really deep diving with a mechanical watch in a future article.

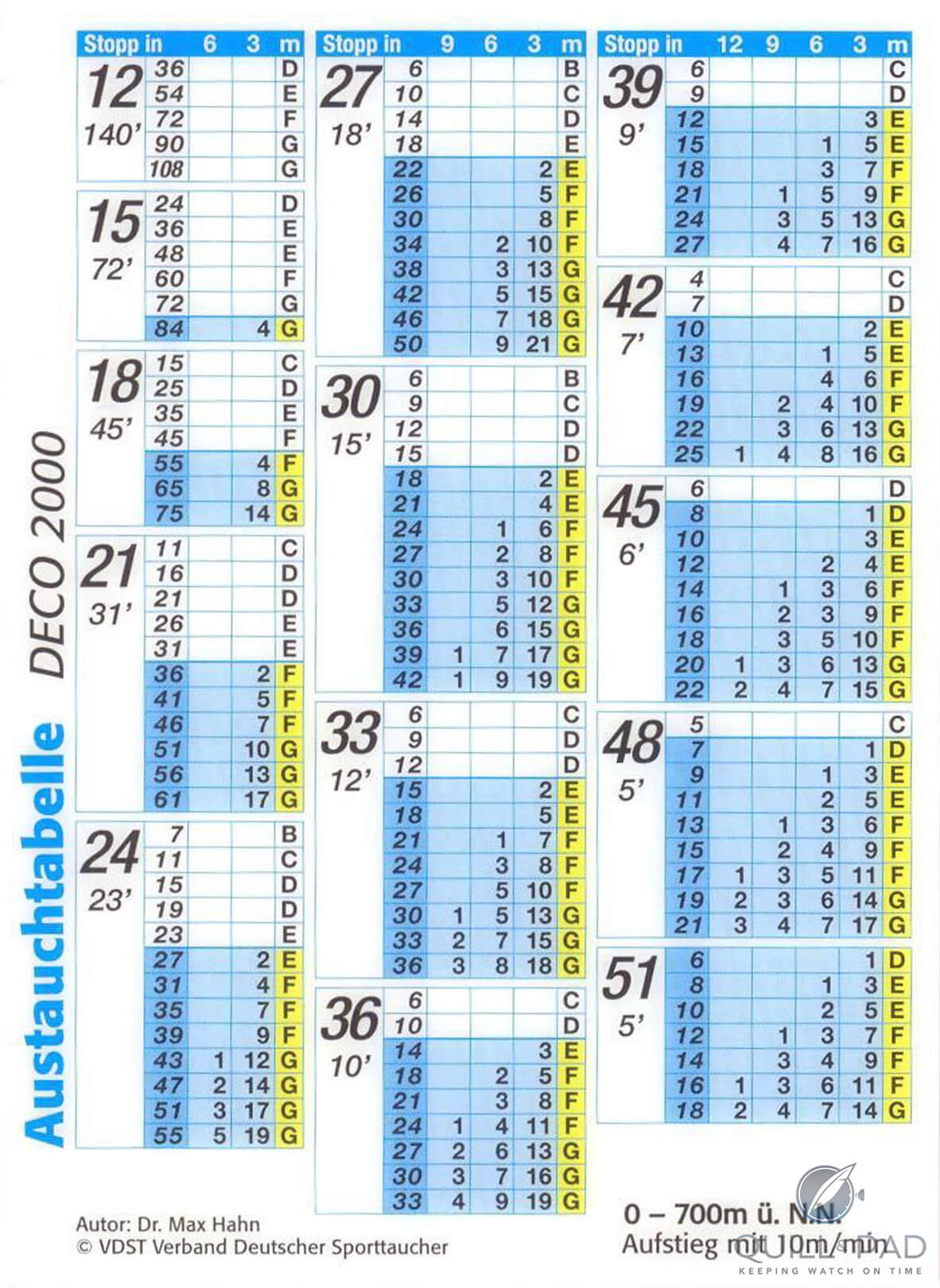

Diver’s decompression table to calculate decompression stops

The 90s rule also doesn’t work at 10 meters, which would give you a time of 70 minutes and more. By that time your air tank would be empty.

Setting bottom time

There is another method of setting the time: the professional way. Professionals first examine why they want to go diving – for example, taking photos of a wreck. Then they figure out the depth of the dive site and calculate the no-decompression dive time before entering the water.

Setting dive bottom time using the bezel’s reference marker

They also calculate the necessary air supply and whether it will be enough for that dive, including a safety margin of one-third more. Experienced divers know that if something can happen, something will happen.

Now, let’s say the bottom of the wreck is at 27 meters. The no-decompression time is 36 minutes according to the 90s rule, which would call for a twin ten-liter tank of air.

To set up the watch, experienced divers subtract 36 from 60, setting the minute hand to 24, which now counts down 36 dive minutes until it reaches the 60-minute mark. At which point, the diver must begin ascent. This way, divers only have to keep the marker in mind and no confusing numbers. All calculations have been done and checked before the dive.

One more aspect of using the watch as a no-decompression dive timer: the dive time starts at the surface but finishes in the depths when beginning the ascent. The dive time from the bottom to the surface is already considered decompression time. And it is always a good idea to finish each dive with a safety stop of five minutes at three meters.

So when you reach three meters, you turn the bezel counterclockwise until the reference marker is at the minute hand and check for five minutes. You’re in the shallows, your brain works again, and you count down five minutes.

Looking at the bezels of serious diving watches, we note they have minutes marked between 0-60 and 15. This scale is for timing decompression stops because most stops for the average sports diver are in the 15-minute range.

The attentive reader may have already realized that in measuring decompression time the counterclockwise motion of the bezel is counterproductive: accidentally moving the bezel will lengthen the time, which might bring the diver to the surface too early. Nothing is perfect!

So you like the look of a diving watch, but you’re not a diver. Is the bezel still useful?

Modern daily life provides enough moments to use the bezel as a timer: the perfectly boiled egg or the ultimate al dente pasta, the “no towing limit” at a parking lot or, perhaps most importantly, when it’s time to pick up the kids at school.

I use my bezel quite often, just for the pleasure of using it.

But is there anything else we can use the diving bezel for other than measuring and checking lengths of time? You bet!

Using the bezel as a compass

Saving the best for last, we can use the diving bezel to transform the watch into a compass. Set the bezel’s triangular reference marker between the hour hand and 12 o’clock. Then point the hour hand at the sun. In the Northern Hemisphere, the reference marker is now pointing south; in the Southern Hemisphere the marker is pointing north.

Using the bezel of a diver’s watch as a compass

And this actually works even better under water than on land as it is easier to see the sun – or at least the center of the brightest light at the surface.

Using the bezel as a second time zone

Diving for many is connected to traveling: warm water, tropical reefs, and perhaps wrecks to explore. For most of us (and indeed for me in central Europe), the best vacation spots for divers are far away – hours away, both in travel time and from GMT. So divers are well served with a second time zone on their watches.

Nothing easier than that as a second time zone function is available by using the bezel of your diver’s watch. If you know how to use it.

Using the bezel of a diver’s watch as a second time zone: remember “west is best, east is least”

As a diver you don’t really want to unscrew and pull out the crown all the time. This weakens the seal and might ruin even the best diver’s watch. To set a second time zone on the bezel all we have to do is keep the time set on the hands and put the bezel’s reference marker at 12 o’clock.

Now we only need to remember this easy rhyme: west is best and east is least.

Example I: we want to dive Puerto Rico’s south coast, the famous Puerto Rico Trench. Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and the Lesser Antilles have a five-hour time difference from my home in Germany – and lie to the west. So we move the bezel to 5 o’clock – five hours forward (west is best).

Now the bezel’s reference marker becomes the 12 o’clock marking in our head and thus in our example the hour hand indicates 5:11, exactly five hours earlier than German time (10:11).

Your watch can work for you so much more on vacation: like this Tutima M2 Pioneer (photo courtesy Sadry Ghacir)

Example II: to dive in the Maldives for me means flying east (is least). So I set the reference marker back four hours (to 8 o’clock), putting the local time on my virtual second time zone function to 4:11.

This might seem complicated if you’re just reading the description, but that’s only because as watch aficionados we’re so used to the hand position in relation to 12 o’clock. Changing that perception is a piece of cake.

On your next trip, once you have buckled in and listened attentively to the safety lecture, say to yourself, “West is best, east is least.” And then set the bezel accordingly (yes, on a diver’s watch you have to set “the best” counterclockwise!)

I promise that by the time the aircraft touches down you will have the new setup of your (now) double-time-zone watch ingrained in your brain.

My favorite dive watch bezels

I have two favorite dive watch bezels: the sapphire crystal bezel of the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms for its beauty and the ceramic bezel of Glashütte Original’s SeaQ for its retro look.

The Glashütte Original SeaQ 1969 limited edition

I also prefer the anodized aluminum bezel that Tudor uses to the ceramic bezel of the Rolex Submariner, even if it will scratch after a few dives. Each scratch on a diver’s watch is like a gash in the life of an adventurer, a keepsake if you will.

Doxa SUB 300 Carbon Aqua Lung US Divers

And there is one bezel that shows these gashes more prominently than any other: the decompression bezel of the legendary Doxa SUB. Yes, there are decompression dive bezels, whole decompression tables on watch dials, and even one decompression diver’s watch. But I’ll save that for another story.

Which was first: Blancpain Fifty Fathoms or Rolex Submariner?

Blancpain talks about its Fifty Fathoms as the first modern diving watch, but many credit the Rolex Submariner, and there are those who believe that Panerai was first as it was used by Italian combat divers in World War II.

Blancpain Fifty Fathoms Automatic of 2020

The Blancpain Fifty Fathoms and Rolex Submariner both came out in 1953, but only the Fifty Fathoms had a unidirectional bezel and could safely be used for diving with compressed air. There is much more to it than that, but that’s also a story for another time.

Regarding the first Panerai diving watches: they were actually Rolex movements housed in Panerai depth gauge cases. But they were not used to measure dive time, only mission time. There was no diving with compressed air in World War II! So it was technically not a diver’s watch but a water-resistant mission timer.

Yes, that might be mincing words but also another interesting story for next time.

Enjoy your diver’s watch, both on land and underwater: it’s much more versatile than you may think.

If you would like to learn more about the history of the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms, you might enjoy this two-part documentary.

* This article was first published on March 19, 2021 at The Diving Bezel: The Most Versatile Watch ‘Complication,’ Even If You’re Not A Diver.

You may also enjoy:

Deeper, Further, Faster: Why Do Some Dive Watches Have Helium Escape Valves?

Glashütte Original SeaQ: An Intriguing Re-Interpreted 1969 Diver’s Watch From Germany

Depth-Testing My Seiko SKX013 Dive Watch: Jumping In At The Deep End

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!