Rick Hale: Wooden Clocks Designed And Built As If By John Harrison Except Today And In The USA (Beautiful Photos + Videos)

I know, I know: the title of this story is a hefty one. But I wanted your attention and for a good reason: clockmakers rarely get the credit they deserve. And I believe that Rick Hale is deserving of at least a few minutes of your attention because this young clockmaker is doing something unique by handmaking self-designed clocks out of wood according to some of John Harrison’s principles.

Rick Hale shaping a large wood gear

Hale is not unlike Harrison in that he is self-taught, comes from a whole other vocational background, and works with wood. In fact, his entire clock is made using wood – every part except for just a few tiny brass elements in the gears.

Hale lives and works in Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA. And coincidentally that is also where I attended university. So, on a recent trip to my alma mater, I made a very slight detour on a foggy Sunday morning to meet with Hale at his workshop to get a first-hand idea of what he does.

How Rick Hale found clockmaking through wood

Hale, like all good autodidacts, did not learn watchmaking in the classic sense – or anything even close to it. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English from Michigan State University in 2011 in his early twenties. “And after that I really wasn’t sure what I wanted to do,” Hale said, seeming to me to echo the mantra of a generation. “I thought I wanted to teach, but it wasn’t as fulfilling as I thought it would be in some ways.”

Rick Hale’s wood hands and gearing

After some time spent doing odd jobs, reading, and trying to stay fulfilled in other ways, he got into woodworking.

“Soon after that I moved to Kalamazoo, and – it sounds unrelated – my father passed away in 2012. When that happened, I went through this really difficult time, which is normal, and latched onto getting into the workshop and making stuff. I guess it was coping; it felt like I was trying to escape.” Hale’s father, a mechanic, showed him things that he likely internalized from cars and how mechanical things work.

It was during this time that Hale made his first clock. “It didn’t work; it was very, very bad,” he laughed. “But that was my first foray into this. So that momentous event was like the turning point that kind of enabled me to think, okay, what do I really want to do? Those kinds of things make you question a lot about your life direction.”

Hale began reading about clocks, describing himself as something of a perfectionist and compulsive, which led to him wanting to make his things to a high standard.

Rick Hale KL1

“As soon as I started reading about clocks and the standards to which a lot of the classic watchmakers and clockmakers held themselves, I was just blown away. I was like, these are my people!”

He explained that the hardest part was figuring out how to use wood as a material to make a clock or a watch, which has to be very stable. “But there are ways to use it to your advantage. Or at least not have it be a disadvantage,” he explained. “A lot of that comes with just designing so that the wood can breathe in different directions without warping and things like that.”

Wood for wheels, wood for gears, wood for clocks

I love the idea of combining clockmaking with woodworking, which sees two distinct crafts coming together. Hale, too, admits if he were “just” a clockmaker that he would probably have found it more difficult to find his own voice and his own niche.

“But when you have arts intersecting, there’s a lot of fertile ground, a lot more ways to combine things: what does wood bring to it or what can I do differently? Every mechanism I’ve made has been something that I’ve been inspired to create.”

A wood pulley on Rick Hale’s KL1

Wood is also interesting because it’s a living material. And, being originally from Michigan myself, I like the local aspect of Hale’s work as well; Michigan has much in the way of beautiful nature to offer.

“There’s so much good wood here, especially the hard woods,” Hale agreed. “There’s a lot of old-growth cherry, maple, walnut, oak, etc.”

Rick Hale’s smallest wood gear to date compared to an American quarter

Hale uses the hard and durable lignum vitae for his bushings, rollers, and anything else with a sliding function that creates more friction – parts that would be made of brass in a modern clock.

“It’s very, very dense, wax-like, self-lubricating wood,” he explained of the plant native to the Caribbean and northern coast of South America. Lignum vitae – whose name is Latin for “wood of life” – is the densest wood available on the market.

A wood minute hand made by Rick Hale

However, I was quite curious as to why Hale chose to use this wood – and how he knew it would be the right one for these components.

“I took a cue from John Harrison,” he answered. “There’s conjecture about where he learned that from. The best [answer] I’ve found is in one of the books about him, which mentioned that it’s possible that because he lived near a port that he might have gone to the shipping yard and asked the boat builders what they use for the rudder or other parts that turn or slide.”

Hale also related that for a couple of months he carried on a mental battle with himself over this. “I wanted to use wood for the bushings and everything, but it’s obviously not ideal from a mechanical perspective.” So he just experimented and found that it worked well. “It’s really just an amazing wood.”

A wood gear and pinion made by Rick Hale

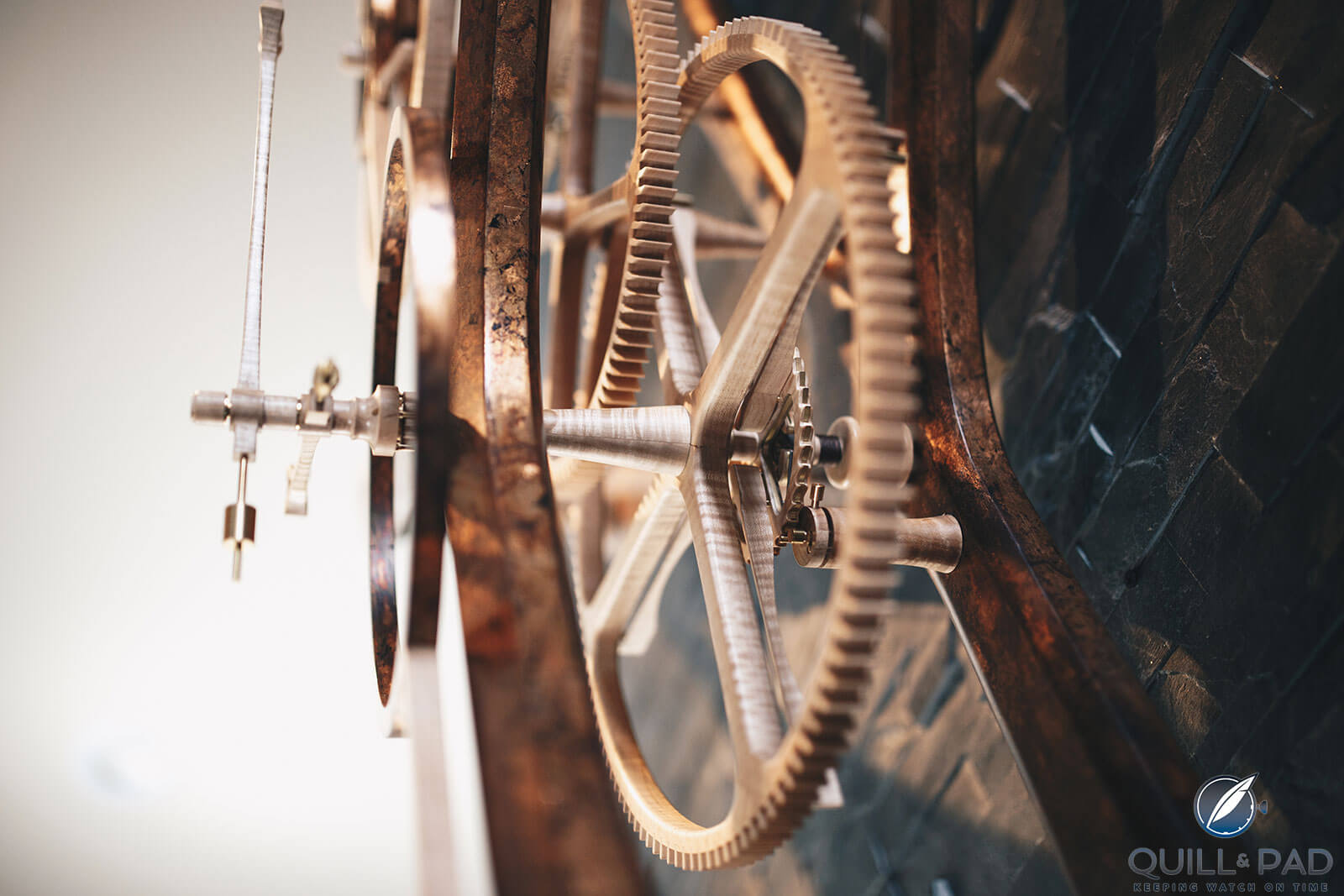

Rick Hale’s KL1 grasshopper escapement

Hale has a lot of practice pieces in his workshop and likely even more in his head. But the large 150 x 90 centimeter timepiece that he’s already designed, manufactured, and delivered is called the KL1. More than a year in the making, he handmade it using solid Michigan maple and overlaid it with copper leaf for a unique patina.

Aside from its impressive size and the fact that it is about 99 percent made of wood, it features one other interesting element that you don’t see every day: a single-pivot grasshopper escapement. A timepiece’s escapement dictates precision as it breaks time into regular (isochronic) intervals. It is the most critical element in the movement as it is responsible for accuracy.

Invented by John Harrison around 1722, the grasshopper is a low-friction type of escapement made for pendulum clocks. Aside from Harrison’s own regulators and his H1, H2, and H3, it has never been widely used. One very graphic modern example of this escapement is in John Taylor’s Chronophage, which is permanently at home in Cambridge, England.

Other modern examples of the grasshopper escapement are fitted to the Burgess Clock B and Parmigiani’s Senfine concept watch, though the latter has not yet gone into serial production.

The grasshopper escapement earns its name by virtue of its motion, and while it is precise when running properly, it is hard to adjust and get to that point. The single pivot used to hold Hale’s version means that it is a “flying” escapement, allowing a clearer view of its motion. That’s an unusual and challenging regulator for an autodidact to choose to use.

A prototype of Rick Hale’s grasshopper escapement

Hale agreed with me, “It definitely felt like going from 0 to 100 a little too quickly in the beginning, but the fact was with wood I really had to avoid sliding friction in every way I could – which instantly ruled out an anchor, recoil, or any of the more basic escapements.”

How Hale came across the grasshopper was almost as unusual: perusing a book that wasn’t focused on Harrison, he saw something about Harrison’s maintaining power and looked him up. “When I saw the grasshopper I instantly knew [it was the right thing for me]: the fact that it just touches the teeth instead of sliding against them. Even though it takes more time and there are more pieces in things, once I came up with a good design for it, it was just the right thing.”

Rick Hale’s KL1 in detail

In essence, this clock functions like any other with a conventional gear train and pendulum, though Hale’s is slightly reworked for use with wood. He uses brass in the center of his wooden gears to provide the teeth with a little more strength.

Even the springs are made of wood; he removes a tiny bit of material at a time until he gets just the right flex. “As soon as people hear ‘wooden springs,’ their faces go white and some wait [to respond], thinking there’s no way that’s a good idea,” Hale laughed.

“But because it’s distributed among four springs you get very little force being used for each of them, and it gives you just enough flex to provide maintaining power. The idea is when you’re winding you don’t really take away the power from the clock, so you keep the pendulum going.”

Rick Hale wood maintaining power gear construction

Then there is how Hale makes his gears. “If you were to try to just make a gear out of one piece of wood, obviously it would warp and do all kinds of crazy stuff, so my method of construction constitutes four staves going out and then four fellows around the edge, so there are eight pieces of wood.”

Hale also constructs them that way because of the wood’s grain. “It really wants to breathe across the grain, and this layout allows that. What you get with changes in temperature instead of warping is a very gentle, uniform material, like the diameter wants to grow or shrink rather than crazy things happening.”

The way I understood it is that by using this construction method, the wood acts more like metal than wood within the movement.

“I’ve kept these test gears around for four years now just to see if they would move or do anything weird, and they’ve stayed very flat and true. So I feel good about my process.”

But, he explained, the one shortcoming with this method is that because of the grain, not all the teeth will have the same amount of strength. To avoid having some teeth be stronger than others, he uses a process that takes a lot more time and effort: he cuts each little groove and makes each little tooth and then mounts them one by one.

Rick Hale rasping a wood pulley

While this process is painstaking, one advantage is being able to polish the faces of the teeth to his desired degree before inserting the teeth. It also allows him to make the teeth thinner.

“It’s the nerdiest thing I’ve ever done probably: I took the way that Harrison laid out his gears and rollers and made myself something like a calculator so that any time I need to come up with a new gear set, instead of trying to figure everything out and spend a day laying it all out, the calculator tells me. If I want to make this gear have 120 teeth and be this diameter, then what diameter does my pinion need to be and how big do the rollers have to be and all that. It makes it a little bit more automatic.

“The upshot of that is any time my clocks have a gear set, it is true to the geometry that Harrison used. That’s something I’ve done in a way to separate my work from other stuff that’s out there. Because even in metal I don’t think there’s anyone really using the chordal pitch gearing layout. Even in the replicas I’ve seen of H1 or H2 people generally use more modern tooth profiles.”

From a mechanical perspective, very slender teeth and very large rollers provide a torque advantage where the friction is lower, something Hale paid close attention to.

Design method

Now a few years into making clocks, Hale uses a CAD software program if he has to design something that he knows is going to require a lot of tweaking. “CAD is nice because it lets me do it all digitally,” he explained. “But as far as big shapes, frames, and overall gear layouts go, generally I just start from a very basic sketch.”

His sketches begin with overall dimensions, from which point he thinks about depthing and mechanical layout. “Sometimes that stuff just has to be figured out while I’m building the thing, but oftentimes I can get a pretty good handle just from a two-dimensional sketch.”

Which means that Hale designs in his head and doesn’t necessarily need computerized help. “It just takes a lot of time; I just keep tweaking it until I find the right shape. This is just two dimensional, obviously, but from there it opens a lot of options as far as contouring goes . . . should this be flat, should this have a gentle curve to it, what does that do with the way the light plays on it?”

The wood gear train in Rick Hale’s KL1

Kickstarter and the general vintage movement help with getting known

Hale works to commissions, but to get them he had to be develop his reputation. So he turned to Kickstarter to show videos and generate word of mouth.

“My philosophy with anything is like if I tell all my friends and family about this thing I’m doing and it doesn’t go from there then it’s probably not that good, you know? So I wanted to start there just to let everybody know,” Hale related and then revealed that his had circle spread the word so much that before long he realized that what he was doing was viable.

“From Kickstarter I found my first commission . . . that kind of got the commissions coming in slowly. And I’ve just gone on from there.”

Hale doesn’t have to work too hard to get these commissions, either, as new clients have approached him directly. And now he has the grace of a waiting list.

This is excellent news because commissions for large, interesting, mechanical clocks are generally not easy to come by. Especially when the whole idea of something being entirely handmade coupled with mechanical timekeeping escapes most people.

Wood gearing in Rick Hale’s KL1

I wondered if Hale’s success can at least be partially owed to the world’s current fascination with a return to vintage and an arts and crafts movement of sorts.

“I think that definitely plays into the initial support and excitement that people had about it. I don’t think people would have been excited if I were to just have told my family and friends that I’m going to start making clocks with no background in it. They probably would have been more concerned than anything. I do think that that movement kind of prepared people for this and prepared me to be as confident or as excited as I was about it.”

For more information or to commission your own clock please visit www.clockwright.com.

* This article was first published on February 16, 2019 at Rick Hale: Wooden Clocks Designed And Built As If By John Harrison Except Today And In The USA (Beautiful Photos + Videos).

You may also enjoy:

The Parmigiani Senfine Concept Features Grasshoppers And Silicon

Tour De France Races Against Both Time And The Time-Eating Chronophage Corpus Clock

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!