Enthusiast (noun): “A person filled with enthusiasm: such as one who is ardently attached to a cause, object, or pursuit.”

Whenever people talk about their passions, they often describe themselves as enthusiasts, passionately devoted to some particular activity, idea, or object. There comes a general understanding enthusiasts might become extremely excited if they begin talking about said passions.

Their specialist topics truly fill the minds and bodies of enthusiasts with adrenaline, keeps them up at night scouring books or websites for tidbits of information, and leads to conversations that at some point invariably turn into a way for them to talk about their passions.

Romain Gauthier Insight Micro-Rotor: the independent boutique brand finally came out with an automatic at Baselworld 2017

Enthusiasts are different from connoisseurs, who may wax poetically about a topic, extolling its virtues and making proclamations about the best of the best but in a more subdued manner.

So while connoisseurs may value similar things as enthusiasts, they have a reputation of being more placid and deliberate, keeping their passions in check rather than letting them take over their emotions.

View through the display back of the Slim d’Hermès Email Grand Feu to the powerful micro rotor for automatic winding

But enthusiasts are akin to fans (a word which is short for fanatics, to provide context), people who aren’t afraid to emote to anyone and everyone about their passions.

In the world of watches, enthusiasts can also be connoisseurs, but when wearing the hat of the enthusiast they take on a role much more expressive than the stereotype of the stoic collector and connoisseur of haute horology.

The enthusiast is just that: enthusiastic – and most likely this personality trait bleeds into other areas of life.

Patek Philippe 5074P and 5078P minute repeaters powered by micro rotors

While automotive connoisseurs might lovingly detail their Mercedes 300SL Coupe before taking it on a cruise around town, automotive enthusiasts might finish up an oil change on their Ferrari 275 GTB before taking it on a mountain run or perhaps to the local track in an attempt to best lap times.

There are similar cars used for very different purposes because enthusiasts tend not to have passive relationships with the things they love. Enthusiasts want to act, desiring to use their watches to fulfill their passions instead of replacing them.

The Fabergé Visionnaire Chronograph has a peripheral rotor around the outside of the dial

I believe it follows for many, if not most, watch enthusiasts that an automatic movement is what is desired on the wrist. Connoisseurs, as I wrote previously in Here’s Why: Manual Winding Watches Are For Horological Connoisseurs, want to connect with their watches, desiring an object to behold and cherish for its beauty, rarity, or complexity.

Enthusiasts, on the other hand, like to wear their watches, use their watches, and maybe even abuse their watches when they utilize them as the tools they are.

Usefulness vs. delicateness

Now I will preface this all by saying that I agree that enthusiasts can be connoisseurs and vice versa, but I’d like to argue that they each represent two different types of behavior and two very different goals for the watches they love. Of course it’s very likely that enthusiasts might have a couple exquisite examples of haute horology that only come out for special events. But the other watches they own probably aren’t safe queens; they are accessories for a lifestyle that is probably more active than not.

Enthusiasts tend to have multiple passions, and those passions can be rather varied and sometimes very adventurous. Automotive racing, mountain climbing, deep sea diving, flying: you name the activity and it is very likely that a watch enthusiast engages in one or more. And when they do those activities, they aren’t taking off their watches in fear of them getting scratched or bumped around. No, they wear their watches as tools and accessories to augment their experiences with their other passions. As such, they don’t tend to use watches that are overly delicate or need a lot of coddling to ensure they are working.

The Richard Mille RM-60-01 Regatta Flyback chronograph boasts adjustable rotor geometry

Many, but certainly not all, high-end manual wind watches fall into that category as they can be very finely finished and feature little protection against an active lifestyle. Oftentimes they will be encased in precious metals that are easily scratched or feature little to no real water resistance. These watches might have complications that can be easily damaged with rough use or have decorative dials that aren’t very legible when participating in a fast-paced activity.

As I alluded to in my previous piece about manual wind watches (see Here’s Why: Manual Winding Watches Are For Horological Connoisseurs), many early automatic watches weren’t even intended to be collector pieces; rather they were being made as wearable equipment, objects that served a functional purpose instead of a coveted talisman. They were tools.

Designs of watches often focused on legibility and usefulness, and automatic winding was the best thing to come along since the invention of the Swiss lever escapement.

While there have always been exquisite horological masterpieces, the vast majority of watches ever produced have been practical time-telling devices for the average person, and the average person tends to just want something that works – perhaps even with as little interaction as possible because, as was becoming the norm, making things “automatic” meant you were living in the future (which some think is a good thing).

Why wind your watch when just moving around will do it for you? That sentiment was extremely prevalent in the middle part of the twentieth century, so much so that the invention of the quartz watch with its extreme accuracy and multi-year battery life nearly killed the entire mechanical watch industry.

Automatics for the “everyman”

As the industry regrouped and was reborn 20 to 30 years ago, two different strategies had emerged for watch companies focusing either on elite horology or quality craftsmanship and practicality. Most of the entry-level watches focused on usability, and due to that a large segment of the market focused on tool-oriented timepieces largely sporting now-reliable automatic movements. The absolute best example is Rolex.

Rolex Sea-Dweller 43mm

Disregarding marketing or nostalgia, Rolex is one of the most practical mechanical watch purchases you can ever make. The brand’s watches have been slowly and deliberately engineered over decades to be extremely reliable, robust, and capable.

And “capable” not in the sense that it can show you the zodiac, sunrise and sunset, or chime the time in three different ways, but capable in that you should never need to hesitate about using the watch for its intended purpose, which is to simply tell the time whenever needed.

Automatic movements became the competitor to quartz because they can be reasonably accurate, and, more importantly, never need a battery change (I know what you are thinking: recommended service intervals, but that is beside the point).

Building upon that, many quartz watches didn’t do too well in extreme environments until well into the 1980s, and since they were being made more and more inexpensively, they began to lose ground as the “choice” solution and instead became the cheap solution for personal timekeeping.

A solid automatic watch was becoming a standard piece of kit for anyone that wanted good, reliable timekeeping in a variety of environments and in a form factor that didn’t make them look like a 14-year-old on a paper route. Adventurers, explorers, extreme athletes . . . many choose a high-quality automatic wristwatch for its durability, reliability, and, not surprisingly, its lineage.

Historically inspired IWC Big Pilot’s Heritage Watch

Pilots would get an IWC or a Breitling; divers would get an Omega or Blancpain; racecar drivers would get a TAG Heuer or Zenith. Or all of these might get different Rolexes. There are many brands that can be considered the go-to watch for specific activities, and pretty much each one will typically feature an automatic movement for different practical reasons.

There are always exceptions to the rule, but when it comes to watches worn by enthusiasts, automatics just make a lot of sense.

Practicality is infectious

The usefulness of automatic movements is hard to argue with when consistency is your main goal. It provides a certain level of assurance that the watch should continue functioning for the foreseeable future. Enthusiasts value that assurance because, in some cases, their lives may depend on it.

Extreme explorers want as many assurances as they can get, so even in the age of digital everything, they may still have analogue watches, gauges, and old-school technology in case the high-tech stuff fails.

And if it’s good enough for the most rugged explorers, well, then it must be good enough for the most incredible horology, too, right? This is where connoisseurs and enthusiasts come together: in the space of high-end watchmaking with a practical twist.

Just because you want something to be beautiful, rare, and complicated doesn’t mean it needs to lose practicality. Plus, some people have the means to wear something horologically (and monetarily) incredible on a daily basis, and sometimes they want it to just work.

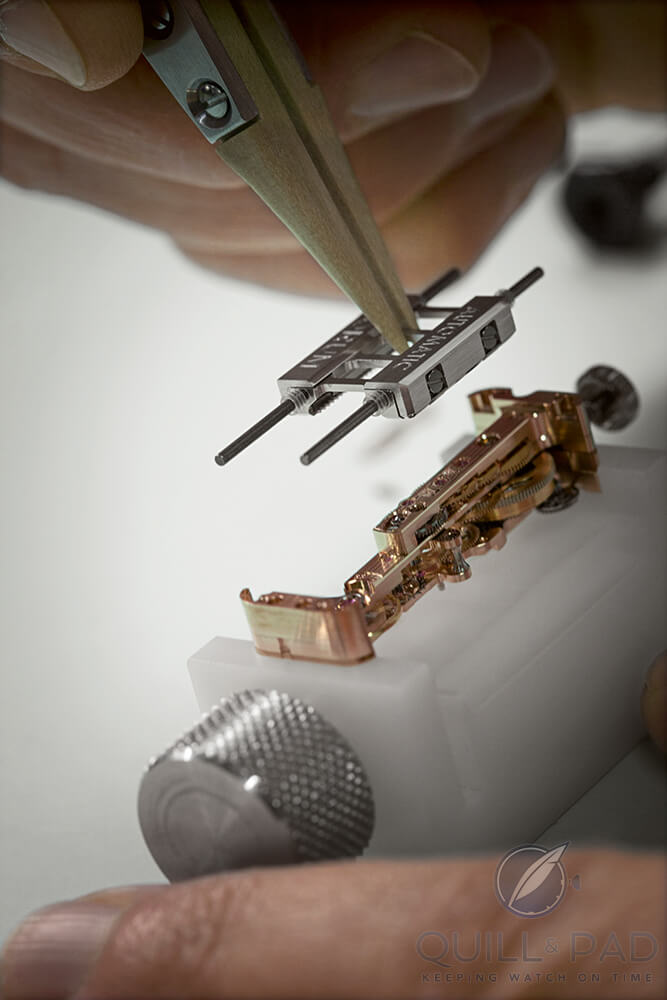

Adding a linear rotor to the Golden Bridge Automatic’s movement

Many high-end watches now include automatic winding mechanisms in a variety of formats to expand on the already fantastic options for haute horology. From the likes of Romain Gauthier, Richard Mille, Hermès, Agenhor, Laurent Ferrier, Vacheron Constantin, Corum, Carl F. Bucherer, Roger Dubuis, Patek Philippe, and more we find peripheral rotors, dial-side rotors, micro rotors, and sliding linear weights; all of these solutions can be added in ways that don’t hamper the view of the movement like the standard center pivoting rotor, and in some cases become something even more interesting to see.

The Singer Reimagined Track 1 uses the AgenGraphe movement with dial-side peripheral automatic winding

This variety of automatic winding options allows for exquisite decoration, ingenious complexity, and a more practical and user-friendly experience that all enthusiasts love. In this way, an enthusiast can have some top-tier pieces without losing practicality, and connoisseurs can have practicality without sacrificing beauty and high-end horology. It really is a win-win situation.

View through the display back to the beautifully finished movement of the Laurent Ferrier Galet Square Boréal

There will always be a desire to have purely classic horology featuring mechanisms that would be familiar to Abraham-Louis Breguet or Ferdinand Adolph Lange, as there should be. But enthusiasts know that a watch that can keep up with their exploits is a valuable commodity indeed.

There can be no consensus on which is better, manual or automatic winding, because they both serve a specific purpose in the modern watch world. But it is certain that while manual winding movements sing of tradition and provenance, automatically wound movements are the true enthusiast option.

Caliber 3500, visible through the display back of the Vacheron Constantin Harmony Ultra-Thin Grande Complication Chronograph, with its half-circle of the gold peripheral rotor clearly visible

So where do you find yourself in this picture? More manual than automatic, automatic all the way, or a nice smattering of both? It doesn’t really matter, as we are all WIS with a devotion to watches and watchmaking that borders on comedic. But to me, one thing is definitely certain: if I am ever lost on an adventure, I know that it’ll be an automatic on my wrist (and hopefully a satellite phone in my pack). How about you?

Happy collecting everyone, and don’t forget to be awesome!

You may also enjoy the article to which this one is a counterpoint: Here’s Why: Manual Winding Watches Are For Horological Connoisseurs.

* This article was first published on August 13, 2017 at Automatic Watches Are For Watch Enthusiasts: A Counterpoint Here’s Why.

You may also enjoy:

Here’s Why: Manual Winding Watches Are For Horological Connoisseurs

Here’s Why: The Chronograph Is The New Tourbillon

Here’s Why The Crown Is The Unsung Hero Of Watchmaking (And Why Rolex Wears The Crown)

Timekeeping In A 5G World: Coordinated Universal Time Blown Away By Ultra-Precision Time On Tap

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Add the Grönefeld Principia to the epitome of an automatic collector’s piece. The full-sized rotor (no micro doo-dahs here) actually adds to the overall beauty, so superbly designed the calibre is.

Absolutely correct! This article and your reply identify the whole reason there is a new trinity in watches. Patek and AP are nice watches but I am not wearing them golfing, diving, fly fishing, auto racing, or tennising. So, Rolex, Tudor and others are selling more because I can use them. The market has changed.

Ah, the active lifestyles we’re all now purportedly leading. Despite the advertising, in whatever form that may take, for tougher, sporty models (I’m remembering Hodinkee’s masterly BS like ‘Travels with a Marathon Watch in Search of Adventure’ where Cole goes out to the muddy Ozarkian wilderness in his jeep, rides his bike, goes kayaking, then swims in digital camo, dear god), aimed at how a customer sees the potential for themself in their mind’s fantastical eye, the reality seems that – in much of the northern hemisphere at least – people are steadily becoming more sedentary (thoughts of WALL-E at the bottom of that family stairlift slope); it seems to be the case that the more delicate high-end models may ironically be the most suitable at this point for daily activities, bar washing the dishes. We’re becoming less sporty and active – you still buck this trend, however. There’s also age to take into consideration: Patek was never aimed at the young.

That’s wot I fink, anyway.

It would be great to own a rolex. And someone to help me with my money I want to help the world and live comfortable

I’m always content. I could only what you create gotta it is awesome . I think I own a science. I forget more than I never. Today is only a dream Have nice day for Gidcrated Himself.

Very good article and good distinction between these two groups of people who are in love with watches!

Sadly, I must admit and the article made it clear to me, that I am just an enthusiast. But it also made it very clear to me, why I selected some of my watches.

With some it is the love for watches, which I learned from my father and remind me of him. Some remind me of people I have loved. Others just spoke to me because of their inner beauty, either their design or their movement and I appreciate not only their bodily forms, but also their mechanical ot automatical core.

But I am fine with being that enthusiastic about my watches. They give me happiness (especially in Covid times), when I hear them click and Humm. They are a moment of tranquility, when I am listing to them or watching it.

So thank you very much for this great article!

I don’t agree with this artificial partitioning at all. The distinctions this is based on rely on convention. The convention that this mold exists so everything must fit into it’s constraints.

But that’s just running with the pack. One can be a connesuer of anything, even quartz watches.

I think the border between the two has more to do with breadth of knowledge of history and detail. Both are enthusiastic.

There is a certain masochism in some collector circles, but it’s inconsistent. With cars, a great manual that requires heel-toe shifting is seen as bread and butter for connesuers, but most embrace the electric starter, hand crank be damned!

Viewing manual wind as the rarefied air and automatics as the more plebian choice is just lazy.

One can make the argument that manual wind was the state of the art at the most significant period of watch creation is a pretty easy case to make.

What opened my personal eyes to this with watches was the Seiko 7A48 movement. It’s quartz, with a 1/10th of a second chronometer and lunar phase complication. It broke my insistence on mechanical only movements and I haven’t looked back.

Rolex? An “everyman” watch?

I’m sorry but I don’t believe for one second you think this.

“Rolex is one of the most practical mechanical watch purchases you can ever make.”

More “practical” than a Khaki Field?

Or a Baroncelli? Or any Seiko?

Or is it just that All Roads Lead to Rolex on every single watch website on Earth?

It is not only tiresome, it is both ridiculous and offensive.